|

A History of 1 Womack Cottages

1850s to 2020s |

A House History of 1, Womack Cottages, Ludham from 1850s to 2020s

by Jane Stevens October 2025

As it looked from 1850s-1960s (Pop Snelling)

1970s-1980s

1980s-2010s Mike Fuller

2010s-2020s

There is the best part of two centuries of history in the bricks alone.

Our house was once a small farm cottage belonging to Beeches Farm. The three cottages now known as ‘Womack Cottages’ were built in the days when most farmworkers were offered accommodation. Other cottages in Ludham Street, about nine, also belonged, as did the brickworks and maltings, conveniently near Womack Staithe for wherry transport.

Curious as to how nineteenth century occupations of farming, malting and brickmaking were associated with our property and its previous occupants, I have pieced together who lived here before 1979 when we moved in, and what life might have been like for them and their neighbours.

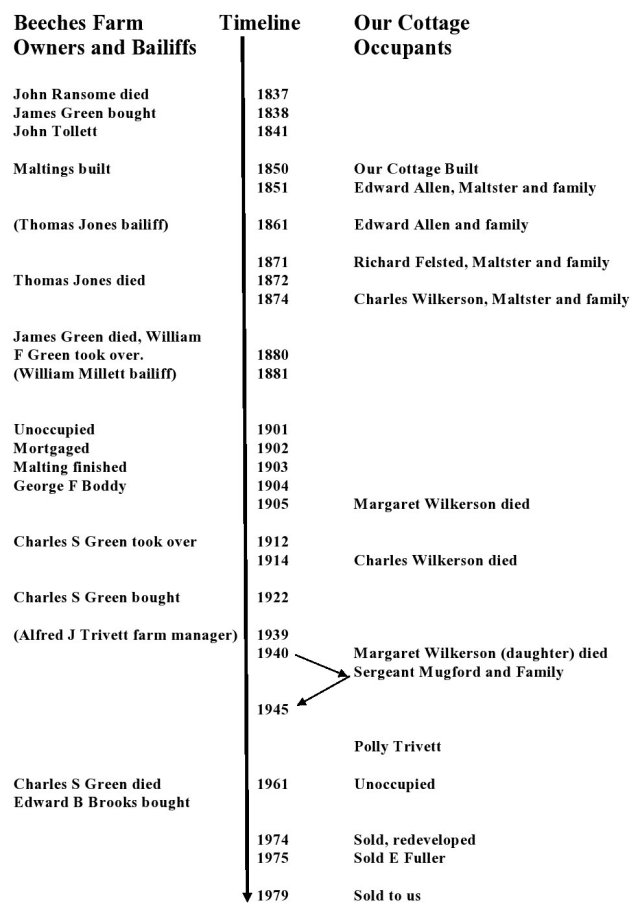

Timeline of ownership and occupancy of our cottage

Censuses from 1841 to 1911 record farm employees living in the cottages, including agricultural labourers, a ‘horse man on farm’ as well as maltsters and brickmakers, mostly with a wife and children. Many were short term occupants and occasionally one cottage would be uninhabited. Unusually, our cottage was lived in for more than 60 years by the same family, the Wilkersons. Charles Wilkerson was employed as maltster and brickmaker for the Greens family in 1874 and remained after retirement with his daughter. She lived there until her death in 1940. One hundred years after they moved in the house was literally elevated from an employee’s tiny bungalow to a two-storey, privately owned family home.

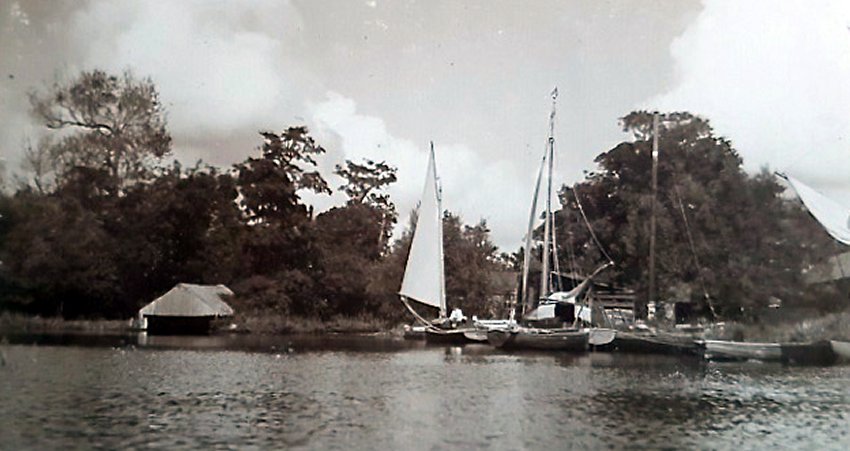

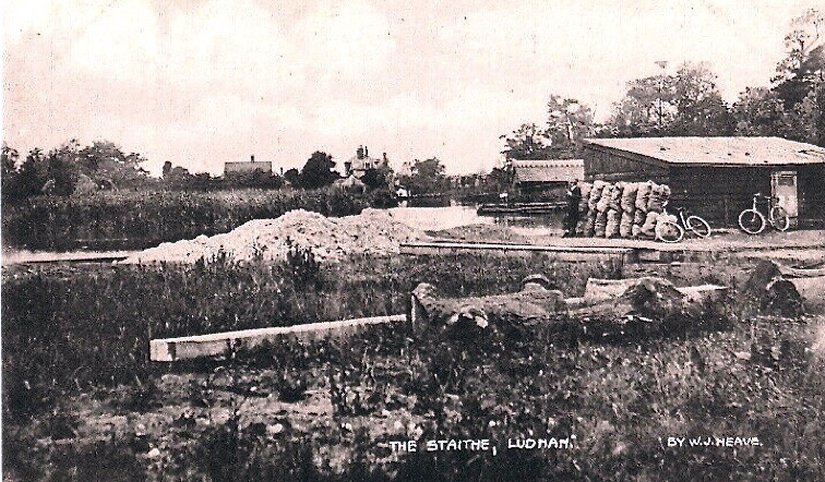

Maltings and brickworks in the background, a Ludham visitor 1875

Womack Water Staithe was specifically allotted at the enclosure of 1800 to the Drainage Commissioners as a parish staithe. For the residents of the cottages it would have been a busy, noisy, smelly place, exciting for kids, who are always trying to have fun, with plenty of exchange of news to relieve daily tedium.

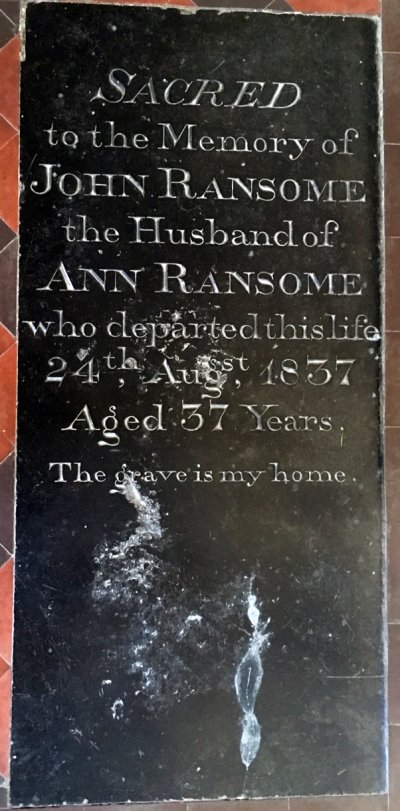

1837-1873 James Green

The oldest part of The Beeches farmhouse was built in 1723, with brick barns dated 1745, 1748 and 1797. Two large Beech trees grew at the entrance to the Beeches Farm house until recent years. A second entrance led to the stack yard and storage buildings. One of the larger barns housed a circular horse operated threshing machine. Besides the lovely farmhouse, with orchard extending to Mill Lane, the farm buildings and yards, there was the sand ‘quarry’ and the brick kilns near to Womack Staithe. The farm land also included “Thoroughfare Piece” (now Latchmore Park), part of The Hulver (marshy ground near Horse Fen), osier beds and grazing marshes at Horse Fen, and surrounding fields.

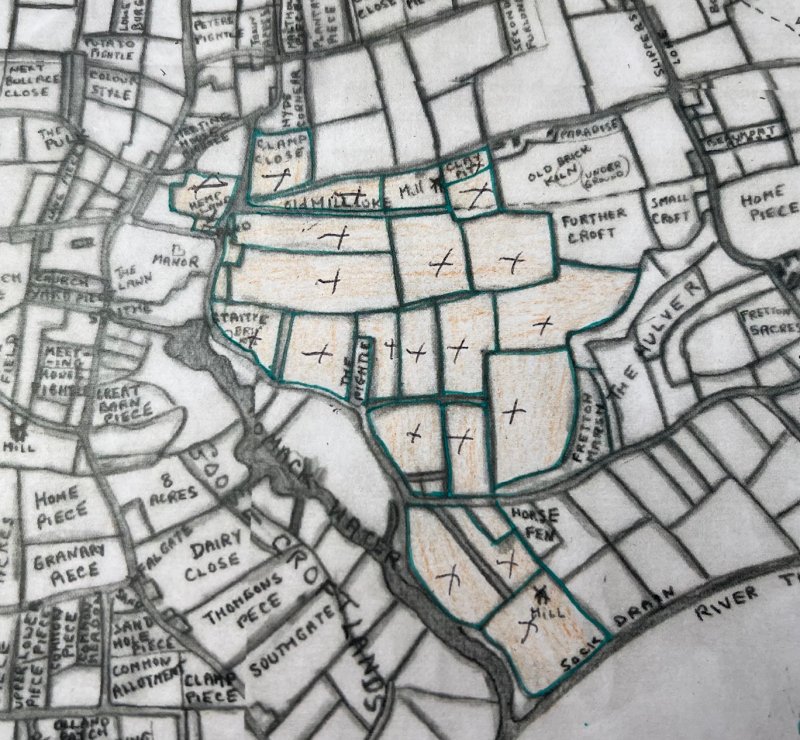

Field Names (http://www.ludhamarchive.org.uk)

Sketch maps showing fields belonging to Beeches Farm. (http://www.ludhamarchive.org.uk)

By checking maps and censuses and talking to locals I believe the pair of semi-detached, brick, farm workers cottages may have been built around 1750. It is likely that our cottage was added on about a hundred years later, at a similar time to when the maltings were built, perhaps even specifically for a maltster to live right next to the maltings and the brickworks. A man could logistically combine the two occupations, compatible by being busy in opposite seasons. Since malt is lighter than barley to transport it made sense to build the maltings near where the crop was grown, and close to the staithe.

The Tithe map of about 1834 shows two cottages but not the maltings, brickworks or sheds. On the six-inch Ordnance Survey map of 1880-1884 not only can we see all three cottages, but also two lean-to washhouses and the external staircase.

The maltings, brick kilns and brick yard layout is clear. Workers would essentially need to be living within easy walking distance of work.

Each of the semi-detached cottages, originally thatched, comprised one room downstairs with a fireplace and a walk-in pantry or scullery, with a marble or slate shelf to keep things cool, and one room upstairs. This was most likely accessed by a “stairhole” -a ladder through a hole in the ceiling.

The outside brick turret staircase would have been added later. A neighbour who saw inside during renovations in 1974 when the turret was removed told me there were sections of wattle and daub in the upstairs wall dividing the two cottages, either side of the central chimney breast. At some point the downstairs had uneven red-yellow bricks set on the earth floor. There were windows on all sides, including the staircase, with outside doors front and back. Lean-to washhouses and outdoor toilets with pantiled roofs were built later on the north side. The one on the middle cottage was right by the front door, and on the furthest cottage it was at the far end. Each has a chimney, suggesting it was a ‘washhouse’ with a copper and fireplace under.

There was the weekly lorry collection of ‘night soil’, also known as ‘the honeycart’. Mains sewerage arrived for most of the village in 1974 where previously it had only existed in School Road from the wartime Forces system.

Built of brick, most likely from on site, around 1850, with pantiled roof, our cottage was typical of the style that some wealthy landowners or independent farmers provided for their farmhands, generally free.

It had a main room and kitchen and two bedrooms, in a single-storey. The floors would most likely be hard earth at least to begin with, only later having bricks or pamments laid on the earth.

The structure of the cottage stayed the same for about the next hundred years.

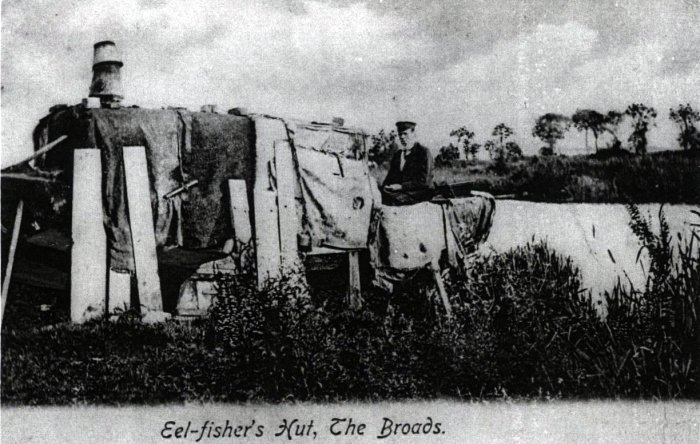

This photo of the cottages was given to us by Cyril Hunter's daughter, Jennifer, taken around the late 1950s when she lived with her family at 'Green Corner' at the end of the lane. At the far left you can just see there are two chimney pots sharing the chimney stack, one for the scullery wash copper, the other for the main room fireplace for cooking. Two further rooms were bedrooms.

I’m not sure exactly where drinking water would have come from, but most properties had or shared a pump from a bore hole or well. There would certainly be at least one at the farm. Would they have collected rainwater?

In the garden I have found some evidence of daily life of previous occupants. There are pieces of thick pot storage jars, earthenware cooking pots, more delicate blue and white china, a piece of very thin green glass, which was perhaps a scent bottle, pieces of clay pipe stem, a flat iron and, most delightful, a child’s tiny china doll head, only one inch tall.

Daily Life

The house deeds mention the cottages as part of Beeches Farm about 1880 as:

"Messuage: farmhouse, three cottages, barns, stables, yards, gardens, lands, and hereditaments thereto, and also freehold land near Ludham Street, formerly of John Ransome (of Potter Heigham) and afterwards of James Green (of Wroxham).

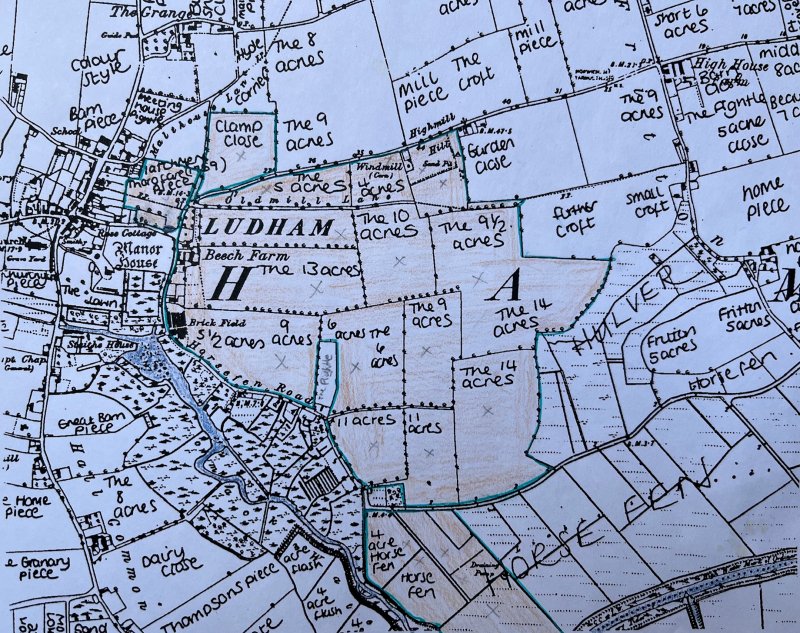

John Ransome died of ‘Consumption’ aged only 37 on 24th August 1837, leaving his widow Ann with at least six children. He must have been a man of some standing because there is a granite/ marble memorial stone in the chancel floor in St Catherine’s Church.

John Ransome’s memorial stone

The sale was listed in Norwich Mercury and Norfolk Chronicle 14th July to take place Sat 4th Aug 1838 at The Angel Inn, Market Place, Norwich, 4pm.:

“The estate was for many years in the occupation of late owner Mr John Ransome, and in the highest state of cultivation. Divided into lots including lot 5: ‘a very compact and valuable Farm, upwards of 202 acres of exceedingly productive arable and marsh ground, with a well-built comfortable residence, very good garden in which there is a summer house. Double cottage, Drainage mills, 2 excellent brick and thatched barns, granary, riding and cart horse stables with lofts over, large chaise House, superior Bullock and Wagon lodges, piggeries, cow houses and other convenient out buildings.”

The farm passed to the ownership of James Green, remaining in that family until 1961.

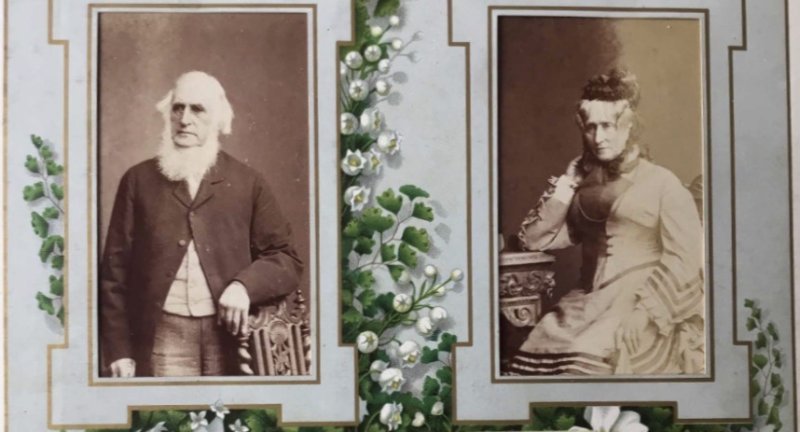

James Green and Sarah Spurgeon, photo by Erica Bailey

James Green, born about 1791, had married Sarah Spurgeon on 7th December 1822 in Mulbarton.

The Greens were a large, well-heeled farming family, owners of land, property and businesses in Wroxham, Belaugh, Plumstead and Ludham. These included brick and tile making. Their extensive maltings and "Maltings (boat) Yard" was adjacent to the freehold family house ‘Grange Farm’, just below Wroxham Bridge, now part of the site of Faircraft Loynes Broads Tours. One of James Green’s biggest and fastest racing yachts was “Enchantress”, built about 1800. In the 1850s he was ‘one of the most ardent supporters of Wroxham Regatta Week, and each year he entertained largely upon his houseboat’. However, “Enchantress”, once his pride and joy, had sadly ended her days in the 1930s as a tourist passenger motor boat, with windows on high cabin sides and a roof deck, operating from the Greens’ own Old Maltings Yard. She was often moored in Womack Water.

At least two of his five sons - Henry Prescott Green and William Frederick Green, were also talented yachtsmen and each oversaw the Beeches Farm in turn.

In contrast, many of their employees would have minimal free time, having to work long hours. The men might engage in social activities including drinking in one of the village pubs. Sports festivals were popular pastimes from 1817, which included wrestling matches, foot races, jingling matches (blind man’s buff with everyone blindfolded except the bellringer) which was fun to watch, jumping in sacks, wheelbarrow races, whistling matches, grinning through a horse collar and jumping matches, all of which were very entertaining.

From 1820 the economy of the country had grown rapidly as the British Empire expanded. At home there were improvements in agriculture as tools went from being primitive wooden implements to sturdy iron tools. With mechanization and land enclosure leading to bigger fields and the practice of crop rotation increasing yields, fewer labourers and horses were needed.

By 1837 there was high unemployment, leading into the 1840s known as the ‘hungry years’. However, from the 1840s rail excursions were possible for those who could afford the time and money. Trains went from Norwich to Yarmouth, Leicester or Loughborough, London or Lowestoft.

In 1841 John Tollet, 40, (of independent means) was living in the Beeches farmhouse with his wife Ellen and two daughters- Julia 7 and Augusta 3. Thomas Jones, 30, ag. lab. lived in one of the thatched cottages as did ten-year-old Elizabeth Gravener. The lane was recorded as ‘Winhook’ at the time.

When rural people rarely ventured beyond the nearest market town, there being no other entertainment immediately within reach, the circus would travel to the audience. George Sanger and James William Chipperfield took theirs to visit most villages, especially if the population was over one hundred. It was still costly so if you couldn’t afford a ticket you could have almost as much fun by walking a few miles to watch the circus parade along the roads to a nearby town.

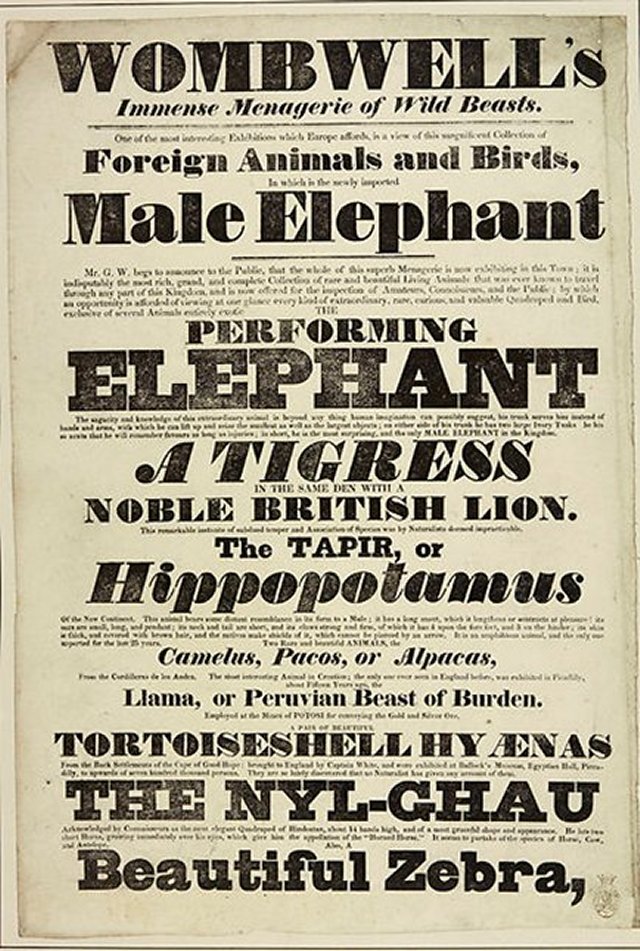

In 1845 a tiger broke free travelling through Potter Heigham causing terror in the village. Fortunately it was soon re-captured unhurt and no one was injured. Menageries such as Wombwell’s Immense Collection of Wild Beasts were also popular. There might be alpaca, elephant, lion, panther, polar bear, tapir, tiger, peophagus (yak) and rhinoceros, accompanied by a brass band.

Posters for Wombwell’s Travelling Menagerie

© National Library of Scotland Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC-BY)

Another name of note was “Manders’ Grand National Star Menagerie” which operated from 1850 to 1871. It was stationary in Norwich for a few weeks before touring the provinces from Suffolk to North Norfolk. The people of Ludham were lucky that the show travelled here in February 1868.

The census of 1851 records “Malthouse Road” as being between Beeches Farm and the broad, after Rose Cottage and the Manor’s Yarmouth Road entrance. It shows probably the first inhabitants of our house as Maltster Edward Allen, 64, his wife Sophia, 60, son William, 26 also maltster and his wife Thirza, 20. Their neighbours in the thatched pair were Brickmaker John Cunningham, 45 and Farm Labourer John Thirtle, 27 and their families. Thomas Jones had moved into the farmhouse with his family as Farm Bailiff for James Green.

In the 1850s entertainment ranged from ‘donkey racing, jingling matches and smoking competitions, [rolling and lighting?] through diving into water or flour for oranges and money, to climbing a greasy pole and eating hot dumplings (which might still be happening in some parts of the world). Most rural fairs, circuses and menageries declined and were finally closed as better rail and road transport allowed access to larger fairs in towns. However, Ludham continued to be visited by Underwood’s fair until well into the 1970s. Originally a market and a hiring fair, the Trinity Fair used to be held at Stocks Hill in June. Latterly, from at least 1928, Charlie Green at the Beeches Farm generously allowed it to be held on his horse meadow field, still on the Thursday and Friday after Trinity Sunday, and coinciding with school half term or ‘Whit Week’.

The 1861 census shows that Edward Allen had retired as maltster in favour of Richard Felstead, 39, but stayed living in the cottage with his wife and daughter Harriet May. The Felstead family were in ‘The Street’, I guess in one of several cottages there also owned by the farm. William and Thirza had moved out. Perhaps they had started a family and maybe he had another job. The census records that John Cunningham was still next door, with children and grandchildren. In the third cottage was Judith Garrett, 77.

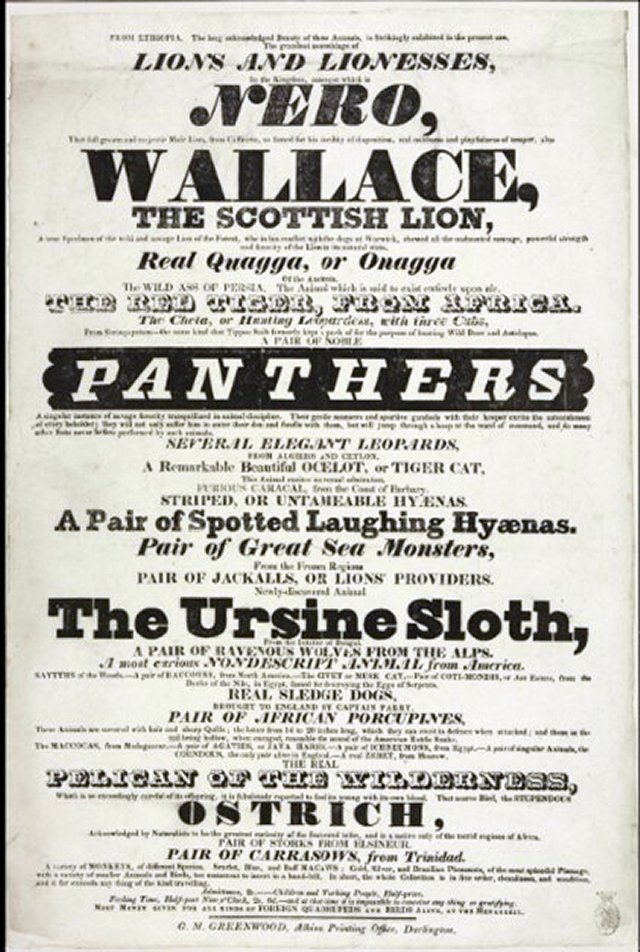

Edward Griffin, 30, ag lab- was recorded as “not in a house”, he was living on his eel catcher’s boat on Womack Staithe.

Mike Fuller's copy of Pop Snelling's postcard

Mike Fuller captioned the picture taken from the negative as Ted Griffen on his boat at Womack Water. Clifford Kittle and other boys used to bung up the chimney, then run away… to smoke him out.

In the 1860s water frolics were popular, which ultimately became regattas, involving rowing races and aquatic sports, drinking, food and band music, decorated boats and fireworks. Horse racing, boxing and prize fighting were enjoyed at all levels of society. Other pursuits included the ballroom, card tables, bowling, cricket, fishing, cycling and reading. Children might go looking for birds’ nests to take the eggs. When Womack Water was frozen there would be skating or a game of bandy. The older youths might have spent time at the pub, playing darts or bowls- there had been a bowling green at King’s Arms since at least 1831, but Public Houses were really only open to men. 1864 Newspaper reports of Thursday Feb 25th reveal that the ‘Ludham Open Coursing Club’ for chasing hares or rabbits held its first meeting, running the dogs through Ludham Marshes, in November 1877 there was news of ‘resuming this once celebrated coursing meeting’ and in 1883 of a meeting ‘near the Ludham Holmes, (marshes) renowned for its coursing ground’. Rabbit coursing for ‘peasants’ emulated hare coursing for the gentry. There would be drinking and gambling, with associated anti-social behaviour.

On 27th August 1864 both the Norwich Mercury and the Norfolk Chronicle ran a report of the Smallburgh Petty Sessions before Sir J.H. Preston, Rev. T.J. Blofeld, Ed. Wilkins and R. Rising Esq. A pub brawl in which Sam George, waterman, Richard Felstead, maltster and Edward Allen, labourer, badly assaulted John Wright, of Ludham, gardener, on Saturday 6th at Ludham, King’s Arms. Sixteen men had gone to the blacksmith’s shop to hang and grind scythes ready for harvest, then to the pub to collect their allowance of 6d per man for drink. (I wonder how much beer would that buy?) They taunted John Wright, saying he was no harvestman and so on. A slight touch turned into a fight. They knocked him down and ten men kicked him. He was so badly hurt that he had to be taken home on a wagon. Not only did he lose his harvest but he couldn’t work again. The men were charged with ‘beating him in a most cruel manner’. All were fined £1 with costs of £1.13s 4d. or a month of hard labour- they all paid immediately.

On 9th Jan1869 The Norfolk News report from Smallburgh petty sessions said that ‘George Felstead, William Thirtle, William Grapes and Charles Cunningham, all of Ludham, were charged by Thomas Jones of that place, farm bailiff to Mr. J. Green of Wroxham, with having committed malicious injury (I guess that means damage) at Ludham on 17th ult.’ (last month),. They were convicted: the three former were fined ‘with costs, 17s.6d. each, with the amount of the injury and the latter with costs 11s.6d.; in default 14 days.’ I’m sure this is nothing new but I thought it revealing.

By the 1870s improved rail, roads and shipping had advanced communications through travel, the postal service, national newspapers, and the telegraph network, so rural communities were more aware of what was happening elsewhere in England and overseas. The local Eastern Daily Press newspaper was only founded in 1871.

In Norfolk the four-course rotation of crops was originally wheat, turnips barley, clover. The turnip tops were for sheep, the roots for cattle and pigs. Variations included oats and bean, in maybe more than a 4-year cycle.

Marsh meadows such as Horse Fen gave a hay crop in summer before being grazed, then left all winter when they might flood. The hay went to the Stackyard after harvest. As well as grass, pigs would eat barley and greens, horses would also have cooked chaff (chopped straw), flaked barley and roots while cattle could have oats, linseed cake, flaked maize, roots, peas and beans. Barley might be stored ‘on the straw’ in ricks at the farm, then threshed and delivered to the malthouse store. Barley straw could be used for animal feed and bedding. By the late 1870s at least two thirds of all corn was cut and threshed by steam machine, contracted out. In the 19th century Barley grown and malted on Beeches Farm could be stored in one of the barns, until ready for sale, planting or animal feed.

The change from horses and hand tools to fully mechanised steam power meant farm machinery was far more efficient. In addition, there were huge imports of cheap grain from the American Prairies and then refrigerated meat from the Australian territories. Together with cheap railway and steamship transport, the price of homegrown wool, grain and dairy produce crashed. Also, the winters of 1879-1881 were the worst successive wet, severe winters known for a long time, so failed harvests and animal diseases were common. Many farmers left farming altogether. The four-year rotation of turnips, clover, barley and wheat became five with sugar beet. Landowners diversified, for instance into carting, dairying, fruit orchards or market gardening. While the population at home had doubled from 1821 to 1881, numbers emigrating grew steadily. Agricultural labourers’ wages were the lowest in the country compared with other occupations. Rents declined sharply, farms changed hands, old loyalties were dissolved and standards fell, weeds were left to seed, drains to choke. Was Charles Wilkerson taken on at The Beeches because the Greens’ focus shifted to malting, brickmaking and beef cattle as a consequence? James Green had taken on new opportunities as they became available to him, just as farmers currently adapt.

In 1871 Charles and Margaret Wilkerson were living in Lower Street, Hoveton St John, part of the Blofeld fruit farming estate. He was maltster and agricultural labourer, though the malting may have been for James Green. Their children were all born there: Charles William the eldest, born 1861, Margaret, born 16th April 1863, John, 1865, Philip, 1866, Harry 1868 and Sam, 8th May 1870. Sarah Ann was born the next year, 16th February 1872.

Meanwhile, Thomas Jones has been at The Beeches Farm so long that it was referred to locally as “Jones’ Farm”. Thomas was now a widower, a Farmer of 230 acres, with nine men and six boys working under him. In the 1871 census his three daughters Almera (26), Ellen (24) and Emma (14) were all living at home, and they had a visitor Ann Jones (53) Unmarried- who might have been Thomas’ sister. Thomas must have been a reliable worker who stayed on until he died 14.4.1872 age 60. He was buried at St Catherine’s Church.

Also in the location of “Womack Water” Richard Felstead (49) maltster moved into our cottage, probably because his predecessor Edward Allen had died. Richard’s wife and three children were there with him. Next door was Benjamin Harmer, 26, labourer with his young family, and one was empty. Further along the lane, after the Harrison, Fairhead and Cox households, the road or track became “Horse Fenn” (marsh).

1874-1912 James Green/ William Frederick Green

Even though nominally James Green’s occupation was still ‘maltster and brickmaker’ in Ludham, he would have been aged 86 in 1874, when Charles Wilkerson was offered the post of brickyard foreman and maltster at Beeches Farm, so it would more likely have been one of his sons William Frederick or Henry Prescott who arranged it. William Frederick Green married in 1874 and was living at The Grange.

Charles Wilkerson moved his family to our cottage to work for James Green as Maltster and Brickmaker, probably in October at the start of the malting season. As unemployment was increasing, some of those not taken on by farmers might hope for seasonal work like hedging, ditching, or harvesting, or do casual work like hoeing, stone picking or threshing. Without security of tenure, including loss of pay during bad weather or illness, Charles most likely viewed his prospects as good at a time when there were more labourers than there were jobs, though 1873 in Norfolk and Suffolk the agricultural wage increased by two shillings to about 12s.6d. More responsibility and security, together with the cottage, must have been very attractive to such a family man. His wife Margaret might have been considering that Ludham had just had a new school built the year before, and the village centre with shops and pubs was closer to walk to. There would be the upheaval of leaving close neighbours and family, but not so far away as to lose touch.

Charles and Margaret’s youngest was Sarah Ann Wilkerson. Her daughter was Margaret Sarah Keeler, born in Martham 15.6.1909, and in the 1980s WEA Study of Ludham she wrote, “My grandparents (Mr. & Mrs. Charles Wilkerson) came to Ludham from Wroxham in 1874. He was in the employ of Mr. Green of Wroxham who had farms at Wroxham and Ludham. My grandfather came as maltster and brickmaker. My grandparents lived in the small cottage nearest to the malthouse and had the use of the piece of land between and behind the malthouse. I have a picture of my grandmother feeding hens on the plot.” The photo is already in the Ludham Archive, but I’ve only just found it, so it pays to keep looking.

Margaret Wilkerson feeding her hens behind the malthouse. (http://www.ludhamarchive.org.uk)

Her granddaughter Margaret Keeler in the Ludham Concert party, 1945. (http://www.ludhamarchive.org.uk)

In the only photo I have seen of the north side our cottage looks much as it would have in 1874. It was taken by Joan (Pop) Snelling in the 1960s. I can just make out the gate in the hedge, the front door and windows on either side.

The north side, Joan Snelling (http://www.ludhamarchive.org.uk)

Accompanying Charles were his wife Margaret and six of their seven children. They would probably have to walk but if they were lucky could use a cart for their few sticks of furniture, pots and pans. They would need two or three beds, a table and chairs, a stool or two, cupboards, and boxes. They might have brought a frying pan, an iron pot, kettle, tongs, a pail and spade, candlesticks, flat irons, toasting fork and a jug and funnel. Some items might have been left in the cottage such as a gridiron for cooking pots to sit on over the fire. There may have been a pair of bellows and a spinning wheel. With just four rooms, they would have to share bedrooms and even beds. All members of the family were required to pull their weight to ensure that the family survived. Taking good care of limited items was paramount, mending and altering as required.

I expect Charles had to start work the next day. Malting began in the autumn, after harvest, The processes involved critical temperature and moisture checks and timing of moving the grain on through the various stages. The season was completed before the weather got too hot in spring so that the sprouted grain didn’t die too soon. His work would include checking supplies, orders and deliveries, though I note on his marriage record he could only make his mark, whereas Margaret signed her name.

Perhaps she kept the maltings records for him, or taught him to read and write.

The outside of the maltings building itself still looks much as it would have done then from the road, though scars in the brickwork show alterations in doorways and windows.

The top floor at the north end of the maltings was for storing barley awaiting processing. Farm carts would drive in from the road to unload sacks weighing 16 stone (1 coomb) through upper double doors, where it was stored for six weeks, to dry and overcome dormancy.

It was still in use as a grain store in the 1940s and on days when it was empty Charlie Green used to say to Mike Fuller and his friends "you boys can go in" if the weather was wet or cold. Mike said they would climb the steps and play on the smooth wooden floor which was "like a ballroom", sliding along the whole length.

The ground floor was the growing floor. Mike remembered there being a chute inside to guide the grain down to the ‘steeps’ below. Barley was steeped or wetted in water for about 8 hours, drained and aired, then rewetted for another 8 hours, soaking the seed and so beginning germination. Ventilation through louvred windows controlled the temperature. Once the grain was soft when rubbed between finger and thumb it was 'couched' or rested in little heaps to gain a little heat, then shovelled or barrowed and spread by hand over the tiled floor. It was turned frequently with broad, flat-bladed wooden shovels to maintain an even temperature and stop the shoots from knitting together as they grew. After a few days the part-germinated grains or ‘green malt’ were thrown by shovel to the kiln floor and left to dry for three to five days, halting growth whilst adding flavour and colour. The upper floor of the kiln had perforated brick tiles on a grid of iron railings which allowed the heat from the coke fire to rise through the malt. I imagine it smelled like a sort of burned caramel or fruit cake type of smell that I recall from Norwich breweries in the 70s. I understand it could still be smelt strongly years after malting had ceased! When finished, the malt was shovelled promptly from the kiln. The rootlets broke off the dried barley easily, perhaps being separated by pouring the malt through wire mesh, and were gathered as ‘culms’ to be sold for animal feed, as they are protein rich.

Charles and Harry in particular would generally be working in damp conditions, which would not be good for either of their health, and we know that Harry later contracted TB.

The south end of the building was for storing the malt for a month before use. It would be in wooden hoppers which would absorb any moisture, keeping the grain dry. A man would climb the white-painted wooden steps, like a ladder with a landing, to reach the upper floor door. He would use the hoist to lower full sacks of malt into a waiting cart. A wherry such as The Lord Robert could carry about 40 tons, bringing sacks of coal and coke, and take on whatever needed to be moved. To help loading and unloading, wheelbarrows with short legs were better for getting into hold, while the gaff could be tied down at tabernacle near the front of the boat and used as a derrick.

When they arrived in the village the new Ludham School had just been opened on 5th January 1874, by Mrs Harwood. Built for 140 pupils on land belonging to A. Neave, Town Farm, on the site of his Great Barn, it had 120 pupils in attendance. However, by November attendance was poor generally as children were singling turnips and crow scaring. The Wilkerson children who could have attended -though elementary schooling wasn’t compulsory for five- to ten-year-olds until 1880- or free until 1891- were: John, for one year as he was already 9, Philip for two years age 8 and Harry for four years age 6. Sam could start the next year and Sarah Ann two years later.

Margaret was 11 and Charles was 13 so they would already be working.

Margaret senior would spend much of her time making sure food and fuel for the fires was available, cooking in a deep pot hung on a hook over the open fire, perhaps in the early days having a pie baked at the village bakehouse in Staithe Road, or the one behind ‘The Baker’s Arms’.

They would have eaten seasonal and locally grown food. Margaret would have used the garden at the side of the cottage to grow potatoes, onions, carrots and cabbages. Watercress, high in iron and fibre, was regularly eaten and it still grows in our dyke. A dense and calorific brown ‘household’ bread was a staple, with home-made cheese. Fish made up a substantial part of the diet. It was fresh, cheap and readily available, Cod, Haddock, Herring and Spratts. The rivers and marshes could provide wildfowl and eels. The most commonly eaten meat was pork. Margaret’s hens would provide enough eggs, the bird only eaten once she had stopped laying.

For much of the year plenty of local fruit was cheaply available from farms in Ludham, at How Hill, and along the Horning Road at Hoveton St. John. Money could be earned for picking, and fruit preservation for winter was well practised.

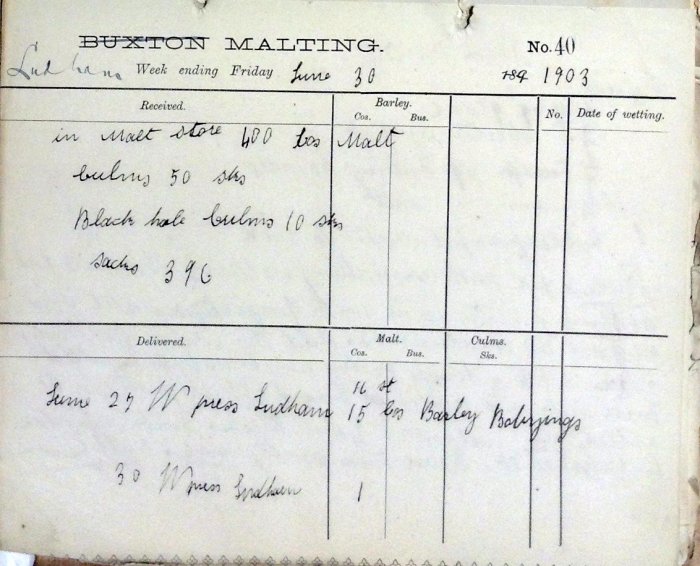

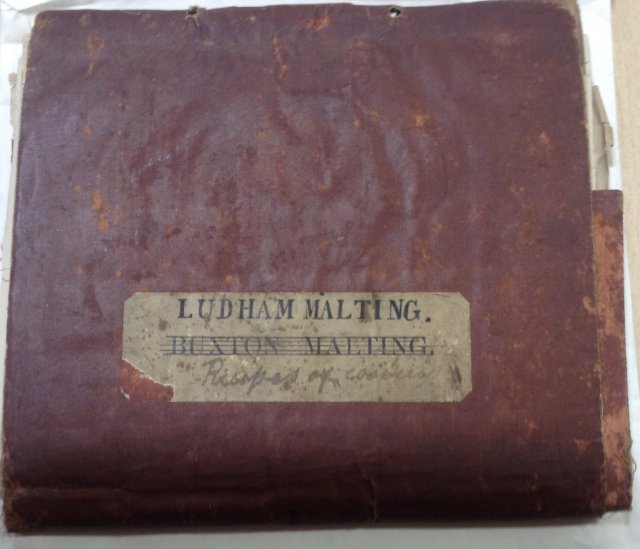

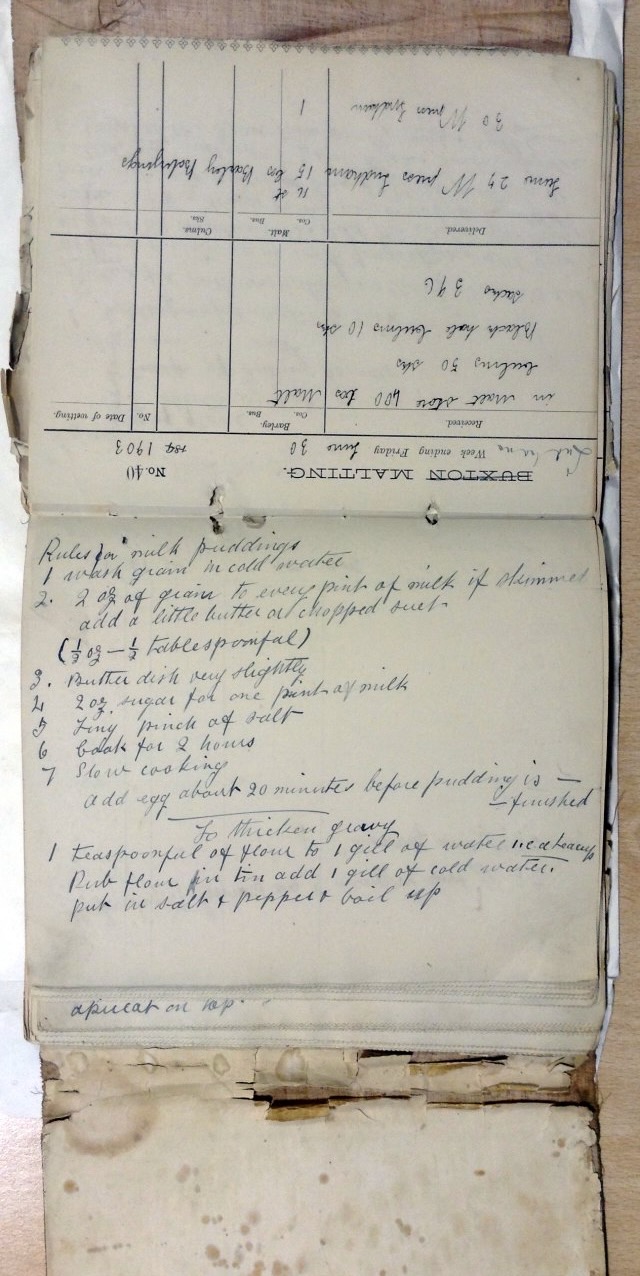

The Maltings record book for 1903, the final year of malting here, shows the frequency of cycles, with a new wetting every four or five days. Malting might take between eight and fifteen days to go through all the stages of steeping, germination and kilning. Our record book shows the weight of barley in and malt out, which farmer and purchaser, deliverer or carrier, naming W. Press and E. Newton, from Womack. Enough barley was received for twenty-nine wettings, or 1,547 coombs, between the end of January and the end of May, with an average of 53.3 coombs per wetting. (One sack of barley weighed 1 coomb, equal to 16 stone or 100kg.) The last receipt was the middle of May, the last wetting the middle of June. Total malt delivered was 1,461.5 coombs, *Bobyings 35 coombs.

The record book was originally printed for Buxton maltings and used there, which makes me think the ’Greens’ owned that too, and that it closed sooner.

The final entry in the record book is for the week ending June 30 1903:

“in malt store 400 coombs Malt

*Culms 50 sacks

*Black hole culms 10 sacks

Sacks 396 (I presume empty)

Delivered

June 27 W Press Ludham 16st 15 cos. Barley Bobyings

June 30 W Press Ludham 1 coomb malt”

*Culms were the rootlets of the sprouted grains, separated from the mat for cattle feed as they were rich in protein. However, I don’t know what ‘black hole culms’ were, or ‘bobyings’.

“When the malting season was over (late spring) my grandfather took over the brick-making. He was foreman of the brickyard and a number of men were employed.” (Margaret Keeler)

The maltings are built of brick and many of those at the base are seconds, most likely rejects from the on-site kilns. There was a small ‘sand hole’ or sand quarry behind the maltings but most brick earth came from the ‘high and low field’ at High Mill. During the autumn it was dug out and left to weather over winter to break down. From the earthhole, known also as the "up and down field" and the "dip field", it was most probably barrowed down Old Mill Lane, past the horse pond at Pit Corner and along Horsefen Road to the brickworks. The bricks were stacked to dry for four days, being turned over after two days to prevent uneven drying and warping. Then they were hard enough to be stacked on end for further drying in long 'hacks' or open sheds, to protect them from the rain or harsh sun before firing. After two weeks the bricks were ready for firing in the kilns, two kilns sharing one chimney. “The bricks, after being fired, were stored on the staithe and many of them were transported by wherry.” (MK.)

You can see the hacks marked on the 1880s OS map.

The building which is currently the butchers’ shop was Thomas Abbot Daniel’s grocers, also selling hardware. The village of Ludham had a population of almost one thousand, with a thriving number of shops and services. There were blacksmith, butcher, shoemaker and cobbler, Knights’ Saddle and Harness Maker, barber, undertaker, boat builder, coal round, carrier, pubs, Church, Baptist Chapel and Doctor. Samuel Taylor Huke was the well-liked Doctor living at The Manor, until he retired to Great Yarmouth in 1875, followed by Dr James Alexander Gordon.

Sunday School being virtually compulsory for all children. The Norwich Mercury newspaper, Saturday 9th August 1884, reported that a crowded Sunday School Anniversary was held in the Baptist Chapel on Sunday 3rd August. Children ‘recited scriptural pieces and dialogues in a most praiseworthy manner, and the choir acquitted themselves most creditably’. A collection was taken at each service for the school funds and a testimonial was presented by Mr. Clipperton to Mrs. Wilkerson on behalf of the subscribers. However, I don’t think the family were Baptist because they had their own children baptised as babies. There would be official days off for celebrations- Christmas Day, The Trinity Week fair, May Day, the Church choir picnic at the end of July, the Chapel outing at the beginning of August and the school treat in the middle of September.

Monday would start early by lighting the fire under the copper full of water, then washing, mangling and drying the laundry outside if possible. The next day was ironing day using a pair of flat irons alternately heated on the fire. In wet weather laundry would have to be hung indoors. Meals would need to be quickly prepared, for example cold meat left from Sunday’s roast, with bubble and squeak.

Wroxham station on the Great Eastern Railway was opened on Oct 24th 1874, just as the family were moving out of Hoveton, and a month after the Thorpe River Green Rail Bridge Disaster on 10th September 1874 at Hart’s Island, Thorpe Norwich. The mail train from Great Yarmouth collided head on with an express Norwich to London train, on a stretch of single track, because the London train had accidentally been allowed to leave Thorpe Station before the Gt Yarmouth train had arrived. Twenty-five people were killed including both drivers and firemen. A Guard and seventy-three passengers were seriously injured. As a result of this and other similar events the system of physically handing over a large ‘key’ token was brought in, where a train could not proceed without it on single track lines. By the 1880s the railway reached Potter Heigham, opening up more travel routes. I wonder how familiar the family became with train trips, whether they could spare the time and the fare, and would they be keen? When they could spare the time and the fare, a train trip to the seaside in best dress or jacket and tie, and hat, would be a treat.

The summer of 1875 was so wet in Ludham that, after a week of heavy rain, on July 21st a clay lump cottage collapsed, where Rice Cottages stand now. Households generally recycled most of their waste by composting, feeding animals, recycling clothing and had no plastic to dispose of but, after a series of cholera outbreaks, the British Parliament mandated that every household deposit their waste in a movable receptacle to be collected weekly.

Around this time Music Halls were popular with all classes of society for the singing, dancing and sketches. As the organ was reinstated churches, musicians gravitated to brass bands in other local organisations such as the Co-op, Salvation Army, Friendly Society and Temperance groups.

Sometimes in the school room of an evening there might be a temperance tea around 5.30 or 6pm, or a lecture or demonstration.

Edison had invented the phonograph in 1877 but it was not in general use until the 1900s.

James Green died on 5th February 1880 age 89 and on 27th November that year the tenancy (from the Manor) that had already been transferred to son Henry was made over to younger son William. He was in his 40s and, according to the 1879 Kelly’s Directory, was already living at The Grange in Wroxham. This probably didn’t affect the way the Wilkersons were living, any more than the repeal of the malt tax that year, or the making and repealing of the Corn laws, or the Swing Riots against threshing machines.

The younger children would have continued at school, perhaps helping pick fruit at How Hill instead of Hoveton House- apples, strawberries, raspberries and blackcurrants. I wonder if chatting to the fruit collectors was the link for Sam going to the Tiptree jam factory in Essex?

Popular activities then were the same as I our youth- building dens, tree climbing, conkers in season, running and playing outside, skimming stones, fighting, messing about in water dykes, catching fish and other creatures, swimming, maybe rowing or sailing or talking to the wherrymen, maybe helping by minding little ones or perhaps jobs no longer common place such as crow-scaring or stone picking.

Womack Staithe 1922

There is a photograph of a similar view Womack Broad taken between 1880 and 1900 by William Denew, which can be seen in the Picture Norfolk collection, pending permission of John Tydeman. It shows two brick buildings in front of the brick kilns. White steps to the upper floor of the malthouse store can be seen.

The 1881 census shows William Millett (39) from Tasburgh was Farm Bailiff, living at Beeches Farm with his wife Sarah (33), and eight children.

Son Albert (15) painter, Daughter Fanny (13), Daughter Rosa (11), Daughter Annie (9), Son Robert (7), Son Adam (5), Daughter Bessie (3), Daughter Kate 11 months. Charles and Margaret were still in our cottage “by Womack Water” with their growing children, Margaret, 17, John, 16, Philip, 15, (both John and Philip were general labourers), Harry, 12, Samuel, 10 and Sarah Ann, 9. Charles continued to work alternate seasons in malting and brickmaking. In the two cottages “near Green’s Malthouse” were Joseph Turner (65) ag lab, with his wife Mary Ann (62), and James Fairhead (60) ag lab, with his wife Jemima (59), and three sons- William (26), Charles (20) and Walter (18). Joseph was still here in 1885, while James and Jemima with William and Walter were still here in 1891. Eel catcher Ted Griffen, now aged and a 50 widower, was living “in hut on staithe” and giving his job as ag lab.

In the 1880s, as print became cheaper and literacy improved, reading matter became more widely appreciated as magazines, newspapers, novels and ‘Penny Dreadfuls’.

The 1883 White’s Gazetteer listed William Frederick Green as farming at Hoveton St John and also Wroxham.

As the Wilkerson children grew and became too old for school they started to work, marry and have families of their own. All the boys moved away, two to Great Yarmouth and two to Chelmsford, Essex. Harry stayed in Ludham. but he died at age only 23. The girls moved away and later returned to Ludham:

Charles William moved to Great Yarmouth in 1877, so not the family home in Ludham, but I don’t know where he was between 1872 and 1877.

He married Eliza Grapes, daughter of George Grapes, Post Office Street, hawker/shopkeeper, in Ludham on June 29th 1884.

Banns of April 1884 in St Nicholas’, Gt. Yarmouth state that she was in Ludham with her parents and he was at 8, Belfort Place, Gt. Yarmouth with Mr. Flaxman, and had been for two months.

They finally prospered in Great Yarmouth, living in some prestigious houses. They had a little family: Charles George was born 23.1.1885 and Margaret Elizabeth was born 6.1.1891.

They moved house in Great Yarmouth every few years, from St Nicholas Road to Well Street. Having been a warehouseman, then grocer’s assistant and finally a commercial traveller. In1891 Albert Knights of Ludham, porter, was boarding with them living 24, Apsley Road. In 1893 they moved to 1, Marlborough Square, in 1902 to Crown Road and in 1916 to Trafalgar Road.

He died Oct 1917 in 68, Crown Road, Great Yarmouth.

Margaret had left home by 1891. She is recorded in Great Yarmouth on electoral rolls from 1904 to 1906, living at 7, York Road and 5, Gordon Terrace (off Crown Road), not far from her brother Charles and his family. After her mother died in 1905 her father would be on his own. The youngest daughter Sarah was about to be married so perhaps it was decided best if Margaret, a spinster, moved back to look after him in his remaining years. She stayed until she died in 1940.

John went to Great Yarmouth and became a warehouseman and then a grocer’s traveller, no doubt influenced by his older brother Charles. On Nov 3rd 1885, aged 20, he was a witness to the marriage of his previous neighbour Harriet Allen to Thomas Robert Bond, in Ludham. Perhaps he returned home for frequent visits. He married Mary Allard 2.4.1888 at St Nicholas’, Great Yarmouth and they had a son John Samuel born 10.10.1888. He died in Northgate Hospital, Great Yarmouth in 1969.

Philip and Samuel went to London, and ended up marrying two sisters. They both advertised for work in The Chelmsford Chronicle. We don’t know if they had already met the sisters. Philip’s advertisement on 11th and 18th September 1885 read “Respectable young man requires a situation under gardener or coachman. Good references- P. Wilkerson, Ludham, Norfolk.” Philip went to Lewisham as a gardener, in 1891 lodging with a family. He married Clara De Maid in 1894 and had three children: Alice Margaret born January 1898, Phylis Tryphena born 1906 and Norman Philip born 1908. He worked as a jobbing gardener between 1901 and 1911. He died 6th August 1919 at the Workhouse Infirmary, Tendring, leaving £582.10s.

On 15th October 1886 Sam’s advert in the Chelmsford Chronicle read: “Young man requires situation in a grocery warehouse, can drive well, 2 years’ experience, good character, S. Wilkerson, Ludham, Norfolk.”

1900 Sam married Alice Sarah De Maid and had son John Samuel Byatt born 29.5.1904. He was factory foreman in the bottle washing department of jam makers. He died aged 70 on 4th January 1941, West Avenue, Clacton on Sea. Effects £1389.17s 8d.

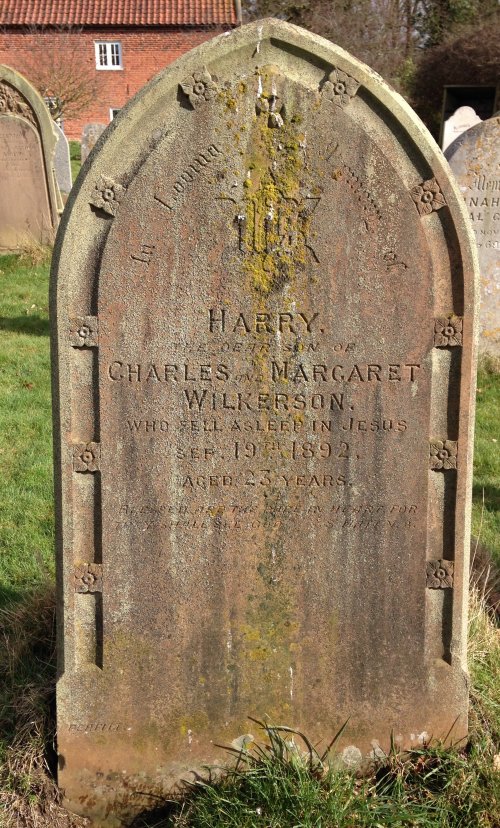

Harry worked with his father at brickmaking and labouring, living at home, although in September 1885 he had put adverts in local papers seeking work as a warehouse porter, ‘willing to make himself useful”. He died of pthisis or TB on September 19th 1892, aged only 23. He is buried in plot G70 in St Catherine’s, Ludham.

Harry Wilkerson's gravestone.

Sarah Ann also advertised for work as her brothers had done. In the Norwich Mercury, Lowestoft Journal and Dereham and Fakenham Times on 17th September 1890 her advert read: “Housemaid- situation wanted in small family as under housemaid, aged 19, 17 months good character, S. Wilkerson, Ludham, Norfolk.” She was a domestic servant age 19 to Vicar Willmott and his wife at the (Old) Ludham Vicarage, Norwich Road. A similar advert was placed on 18th March 1893 in the Downham Market Gazette. In 1906 she married widower George Thomas Keeler, a Ludham born bricklayer, who already had a daughter Cristobel. Sarah Ann had her own daughter with George, Margaret Sarah, born 15th June 1909 in Martham. By 1911 they had moved back to School Road, Ludham. George died 25th April 1917, Sarah Ann died 11th September 1952 and both are buried in St Catherine’s church, Ludham. Margaret Sarah lived until 1990, mostly in Ludham though she travelled abroad too. She was a Sunday School teacher and organist at St Catherine’s Church and was a great friend of Beulah Gowing. Very interested in local history, she was one of the group of WEA students, including Martin Walton and Nancy Legg, who researched the village history and produced the 1980 report. She lived next to Fred Skillern, opposite the school. Was this the house where she had grown up? She died at ‘The Old Vicarage’, Ludham, which was by then a nursing home.

The 1885-6 electoral register shows William Millett “on Green’s farm”, and Charles Wilkerson, Joseph Turner and James Fairhead senior “dwelling house near Green’s malthouse”.

1887 Queen Victoria celebrated her Golden Jubilee and the people of Ludham ‘marked the occasion fittingly.’ After the 1.30 church service they processed behind the Great Yarmouth Temperance Brass Band to the barn and meadow of Laurel’s Farm, where there was an afternoon and evening of sports, a meal, dancing and fireworks. See Pop Snelling’s book for more details.

For pleasure trips and outings, such as a Sunday School visit to the seaside, a steam engine could haul a small group of farm carts at about 4 mph. so would be limited to short distances. People would generally be prepared to walk as much as seven miles. A trotting horse with single rider could travel between eight and nine mph. On market day they might use a local carrier, though that would only travel at three mph and not be very comfortable. Whole village events, perhaps including a parade and picnic or tea, and maybe a Punch and Judy show, would likely be in the vicarage grounds, or a meadow.

Another treat on offer was the cinema in town and the travelling cinema or ‘Bioscope Show’ with steam-powered organ at the front and dancing girls in the intervals between screenings. Also emerging were reading rooms, mechanics institutes, and village social clubs.

The National School had cost 1d per week for children of labourers, 2d per week for children of journeymen and 3d per week for children of tradesmen. Following the summer of 1891, when schooling became free to all, in 1892 Ludham School was enlarged with an extra classroom and the National School was closed.

The 1891 census for Horsefen Road shows Charles (Maltster and Brickmaker) and his wife Margaret both age 56 were still in the cottage with just Harry, 23, living at home, working as brickmaker and ag.lab. William Millett (49) was still the Farm Bailiff, living in the farmhouse with his wife Sarah and three of their children. In the other pair of cottages were

Matthew G. Pearce (24) Ag lab, with his wife Rosa Elizabeth (22)

Daughter Lily Wales (9 months), and his sister Ethel M. (11). James Fairhead was still there aged 70 (brickmaker and Agric Lab,) with wife Jemima and two sons William (36) and Walter (27), both Agric Lab.

After a long time of settled life came a period of shocks and difficult situations for the Wilkerson family.

On September 19th 1892 Harry died, age 23 from pthisis, otherwise known as tuberculosis. We can’t know how he caught it, whether it was rife in the village at that time or whether he was more vulnerable than the rest of his family. Known as a wasting disease, or consumption, he would have had prolonged coughing, maybe feverish, and become too weak to work. From the death certification we know his father was with him when he died.

At the end of October 1893, the Yarmouth Independent newspaper reported a situation of which the impact on the farm and malting in particular could be huge, bringing great uncertainty for Charles Wilkerson and his family:

Under the heading: Important Agricultural Sale Ludham, Norfolk,” it said “Messrs. Spelman (Auctioneers, Valuers and Estate Agents, at Norwich, Great Yarmouth and Lowestoft) have received instructions from W.F.Green Esq. (who in consequence of ill health, has let the farm) to sell by auction on Tues Nov 7th 1893 the valuable FARMING STOCK upon the Ludham Farm”. The stock included sixteen horses, some for work and some for breeding, as well as “36 FORWARD AND FRESH SHORTHORNS on the farm since November, March and April last, now for four weeks on roots. 50 HEAD OF SWINE. Exceedingly good carriages, implements and harness, all fully described in catalogue.”

I don’t have any information about what happened next other than that by the 1901 census the farm was unoccupied, its grist mill, stables and cowshed all empty, and malting ceased two years later. In spite of this it seems that Charles Wilkerson continued to live and work at the maltings for the time being.

In 1894 he put himself forward to serve on the first parish council. Edward Press had ‘land and tenement by Womack Water’, in the end of the maltings building, and jointly with Walter Press at Staithe House. Robert Tillet moved into one of the ‘Malthouse Cottages’ and two years later moved out. Edward Slaughter (36) Teamster and ag. lab. moved in, with his wife Mary A (28) and sons Charles (10) and William (5).

1896 William Frederick Green was still nominally a merchant, maltster, landowner in Wroxham and a brick, drainpipe, tile and pottery maker in Little Plumstead.

For Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee on 20th June 1897 a bonfire was lit on Gorleston beach, including ‘masts and barrels’, but there were no celebrations in Ludham as people said they could not afford to, due to unemployment or low wages. Several people had emigrated to America and Canada because of the financial depression. That November a strong gale brought storms causing floods in Great Yarmouth and at Horsey. Thousands of acres of salt marshes were submerged so the people of Ludham would certainly have been aware of the impact.

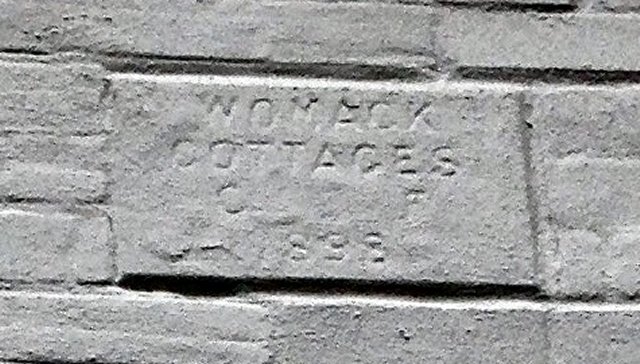

In 1898, two cottages were built near to ‘Little Holland’, which are now known as ‘Little Holland Cottage’. However, Adrian Lupson, the current owner, showed me the builder’s plaque when he knew I was researching the history of our cottage. It says “Womack Cottages 1898 C. F.” It was a big surprise to me because our cottages are known as “Womack Cottages”.

The name must have been changed sometime between 1911 and the 1970s, when the current ‘Womack Cottages’ were renovated and given that name. Confusingly, in the 1901 census, the present ‘Womack Cottages’ were called ‘Womack Walk’.

Builder's plaque, Holland Cottages

In 1899 one of the malthouse cottages was empty, and Frank Davies Knight moved into the other.

In 1901 Charles Wilkerson seemingly continued as maltster, he and Margaret were both 66.

In one cottage were Edward Slaughter (39), Teamster on Farm, his wife Mary A (33), two sons Charles (15), and William (10), his brother-in-law George Wright (23), labourer and fisherman. In the other were Charles Cooke (24), Cattle Yardman on farm, his wife Eliza (26), and their son Charles (1).

Ebeneezer Newton was renting the coal shed on the staithe, distributing sacks around the village by cart.

Newton's shed, 1910. (http://www.ludhamarchive.org.uk)

Walter Press, coal and corn merchant and wherry owner, rented space in the Malthouse to store his goods, transported to and from Womack Staithe. Wherries conveyed anything and everything from clay, stone, hay, timber, bricks, malt, coal, coke and marsh litter (sedge and reed for animal bedding) to paraffin oil, reed, manure, marl, sand and lime. All were loaded or unloaded, stacked or stored by men with barrows, horses and carts at the staithe. There were two little houses on the quay in Great Yarmouth where wherry transport bookings were coordinated. When Womack was frozen, they got saws and cut out blocks of ice, so it didn’t clamp and damage the wherries.

When Queen Victoria died 22nd January 1901, the whole country went into mourning. Shops dressed their windows in black, and everyone was advised to wear black clothing for six months.

The deeds of Womack Cottages refer to The Manor of Ludham Court Rolls showing that on August 2nd. 1902 William Frederick Green took out a mortgage (indenture) of £4,500 on Beech Farm from Harry Edrich of Lingwood (a solicitor?). The conditions were that he:

1. paid interest on the loan at the rate of £3.10s. 0d. % starting on 2nd February 1903, and from after that date on any outstanding at equal half yearly payments, and

2. keep it insured for £4,500 and pay off the loan in seven years.

He may have been expecting to pay off the loan the following February.

I wondered if it might have been for re-investing in the farm, for example more new building, land, equipment and stock, after having let the farm and sold stock and equipment, in 1893. Maybe the national decline in agricultural profits was a factor. At this time he still owned a 14-ton racing yacht named Water Lily.

Alfred Neave may briefly have owned The Beeches Farm around this time, “except one cottage occupied by Charles Wilkerson”, in addition to High House Farm and Green Farm, which together had once made up the old open field known as Bear’s Hirn. He also owned Laurel's Farm.

When A.T.Thrower took on the shop in 1902, Ludham was thriving with four grocers, four butchers and five pubs.

The modern ‘safety’ bicycle emerged in the late 1800s, with two equal-sized wheels, a chain-driven rear wheel and a diamond frame with pneumatic tyres. By 1895 it was very popular and reasonably priced, giving opportunities for independent travel for work or pleasure. You could pack a tent onto a bicycle for a camping holiday. It is likely that some of the Wilkersons owned and rode bicycles. In 1900 a bicycle parade was part of a flower show at Neatishead and in 1911 a slow bicycle race was included on the Fitzhughs’ Ludham sports day.

Railways and then charabancs (motorcoach, usually open topped), and cars allowed people to reach the city as well as towns for musical, theatre, and cinema performances. In 1900 the acrobats and lions of Barnum and Bailey’s Circus could be seen outside The Duke’s Head, King’s Lynn. The Hippodrome in Great Yarmouth was built 1903 by showman

George Gilbert and is still going. It was exotic and the unrestrained enjoyment countered the monotony and hard, unremitting toil of ordinary life. Village entertainment, for those unable or unwilling to travel, could include a magic lantern show, bazaars and concerts, or live music in the home of fiddle, brass instruments, piano and singing.

We think malting continued to operate until 1903 because Margaret Keeler also wrote:

“I have an old book of entries of dealings from the business. The last entry was 1903.” The book is now in the Norfolk Record Office, catalogue reference BR 204/1 as ‘barley receipt and malt delivery book with a record of wetting at Buxton Maltings 1894-5 and Ludham Maltings 1902-3. Re -used as domestic recipe book.’

The book can’t have been started before malting ended in June 1903 but I’m not sure whose it was. If it belonged to Charles’ wife Margaret, she would have to have filled it in a short time because she died 1905. I think it most likely belonged to her daughter Sarah Ann who was married the following year and was likely to have needed the wedding cake recipe. Most of the handwriting is the same, with a long cross on the t. A few recipes written in a different hand may have been added by another person. Sarah Ann’s daughter, Margaret Keeler, who perhaps did the scribbling as a toddler, gave it to the Norfolk Records Office.

I went to have a look and found that besides a few barley and malt deliveries it was full of handwritten recipes, remedies, scraps torn from magazines and a few childrens’ scribblings. Of the scores of recipes in the book, most are sweet. I was surprised to find that so much sugar was consumed. Many are for cakes, puddings and jam, apple and sago pudding, some savoury items like fish cakes, mustard sauce and a few drinks like parsnip wine and ‘a good winter drink’. They must have had an oven of some sort [Dutch?] since many are for baking.

A surprise item of interest to me was simple instructions for how to clean gilt picture frames- perhaps used by Sarah Ann working as a housemaid. “First thoroughly dust them with a clean duster or soft brush and then take some vinegar and water (2 pints vinegar to one water) and carefully rub. Once the frames when dry polish with a soft rag and the frames will look like new.”

Front cover "Recipes of cookery" Norfolk Record Office, catalogue reference BR 204/1

Final maltings entry/ Rules for milk pudding/thicken gravy. Norfolk Record Office, catalogue reference BR 204/1

Even though malting had ceased Charles and his wife were able to stay on in the cottage, perhaps at a small rent. As agriculture changed from horse to steam, then diesel, the number of agricultural workers on the farm was by now much reduced so the cottage was not needed for that purpose.

Walter Press continued to store goods in the Malthouse. Ebenezer Newton, merchant supplying grain and coke for malting, kept his dappled horse at the end of Maltings ground floor, which and occasionally broke out to graze.

From 1904 it seems George F. Boddy was running the farm and living there, I’m not sure whether as bailiff for William Frederick Green or Alfred Neave, or if he was the owner. He seemed keen to support sporting activity. Ludham athletic sports programmes at The Grange cite G. F. Boddy in 1906 as judge, and 1907 as starter and laps counter. He may be in the photo of Bandy players on the frozen Womack Water wearing skate runners and tweed, using foraged curved sticks or walking sticks, to hit a wooden puck.

Playing Bandy on frozen Hoveton Little Broad / Blackhorse Broad’ (Norfolk Record Office).

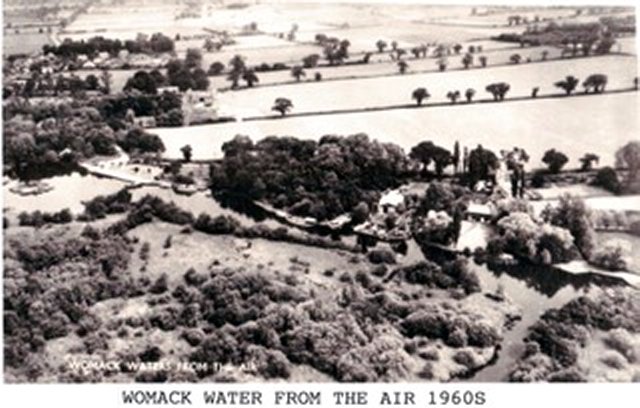

Soon after he arrived, “Acting on the suggestion of boating visitors, several Ludham residents, notably Messrs. G. F. Boddy, W. Lake, and E. Newton, set to work to organise a regatta and aquatic sports in connection with the increasingly frequented Womack Broad.”

There used to be two annual regattas, one a passage race, only open to local boats, along the river to Thurne and back, the other on Womack “Broad”, in August. “The committee barge, gay with bunting, was moored off the Womack Dyke, and the matches … were sailed up and down the confluent River Thurne. An adjournment was then made to a part of the broad between Mr Boddy ‘s boathouse and Mr Newton‘s staithe” for a quanting match, rowing races and the greasy pole.

“Mr. Boddy had, with Mr Newton, and their employees, already prepared his spacious barn. This was seated, draped, festooned, and lighted, and the approaches illuminated with Chinese and Japanese lanterns. Here was held the concert,… Admission was free, and the audience numbered close upon 500. Vocalists included several visitors, whose performances were above the ordinary local level. But the comedian is invariably the popular favourite, and in Mrs. Barr the promoters had a happy acquisition.”

Clifford Kittle said they stopped having regattas here in about 1911 because it was getting too small, weedy and too many trees, so they moved them to near Thurne dyke.

Womack Regatta 1911 (http://www.ludhamarchive.org.uk)

The caption for this photograph is Womack Broad Regatta. Aug 8th 1911. However, it looks as though it is on the river.

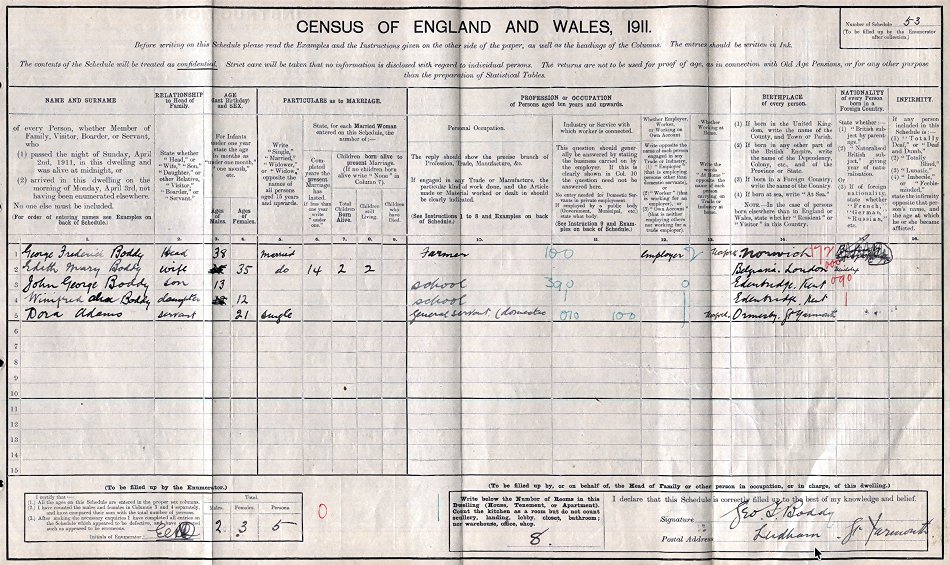

G.F.Boddy 1911

I have found newspaper cuttings between 1904 and 1907 which report that George Boddy, Beech Farm, Ludham often won prizes in the spring shows of the Agricultural Association in Norfolk and Islington, London for three and four-year-old breeding stallions and Shire horses.

When Charles’ wife Margaret died age 71 February 26th 1905 she was buried in St Catherine’s, Ludham on 2nd March. (plot G81) Charles continued to live in the cottage and his eldest daughter Margaret returned. Edward Slaughter left to go to Fritton Street, that year, leaving after nine years.

The 1908 Register of electors shows William James Punchard living in one of the cottages. He would have been working on the farm. His daughter Ethel Maud was born in Ludham on 3rd January 1908. He must have moved here sometime between March 1905 and January 1908. Ethel Maud was the fourth daughter born to him and his wife Caroline.

The 1910 Register of electors shows that James Philippo moved in, from Fritton Street.

The 1910 Finance Act documents describe the staithe as ‘Piece of open land by Womack, the property of the Drainage Commissioners’. At the time it was being leased to E. E. Newton. His large, dark, timber shed, value £15, was directly opposite the site of the kilns, from where he operated his coal business. The staithe was generally scruffy with no particular pathways, only being smartened up later, after several years of petitioning to the owners and users. When they finally built the staithe up, in the 1950s, underneath, about 18” down the working party found big white flints that had been put in first. We have some of the same making a ‘rockery’ at the front of our drive and wonder if they were surplus to requirement for the staithe, and Charlie Green thought they would be useful. Some have said they were used as ballast in wherries.

The 1911 census on 2nd April lists George Frederick Boddy (38) as farmer,

with his wife Edith Mary (35), son John George (13), daughter Winifred Ada (12) and general servant Dora Adams (21), the farmhouse having eight rooms.

Charles Wilkerson, age 76, is now described as ‘widower, retired maltster’, his daughter Margaret as age 47, single, housekeeper, and the cottage having four rooms. Daughter Sarah Ann Keeler moved back to School Road, Ludham with her husband and daughters. James Philippo moved out, after less than a year, leaving the cottage empty. William James Punchard went to another job as Horseman on a farm in Attlebridge.

From ‘Find a grave’, Memorial ID 15353846

This photo was taken in 1916 of Private William James Punchard. He joined 7th battalion of Norfolk Regiment, disembarked in France 10.12.1915 and was killed in action France on 8th March 1916.

His brother, John, took his place as Horseman at Beeches Farm and moved into the three rooms with his wife Laura Maria (24) and baby daughter Laura Maud (7 months). There is a lovely photo of a very smart “John Punchard the Teamsman of Ludham, holding a shire stallion, Stalham” in the Norfolk County Council “Picture Norfolk” collection.

The Horseman or Teamsman was in charge of, and responsible for, the men and the horses that did the heavy work. There was a strict hierarchy of procedures and rules to observe so the horses were well fed and groomed, with great respect and pride shown by the team. The teamsman would be up at 5 am, to see to the horses before his own breakfast. Horses had to be fed an hour before they could be led out of the stables to whatever work was on that day’s list- ploughing, harrowing, seeding, hoeing, thinning or harvesting- to give them digestion time. Agricultural labourers began work at daybreak and continued, with refreshment breaks, till 3 pm in the winter and dusk at harvest. There would be horse drinking ponds at each farm, that of the Beeches was on the corner opposite Old Mill Lane. After a day’s work in summer the horses were led to pasture or marsh. One could be ridden and one led, and in the morning they had to be caught and brought back. I found more information and pictures about being leading farm hand in the book- ‘Ask the Fellows who cut the Hay’ by George Ewart Evans.

From the 1912 Register of electors we see that George Boddy was living at The Beeches and also farming at Ropes Hill, Horning. Charles Spurgeon Green took over The Beeches Farm later that year.

Still next door to Charles Wilkerson and his daughter Margaret was John Punchard with his family. He stayed in agriculture in the region, moving to Dilham, where one son became a tractor driver. John lived until he was 76, being buried at St Nicholas’ Dilham. His wife later lived at Meeting Hill, Worstead. She lived until aged 80 and was buried with her husband, leaving over £900 to their married daughter.

1912-1961 Charles S Green

Directories show that in 1911 and 1912 William F. Green held freehold land Yarmouth Road, Ludham, even though he lived at Belaugh Grange, Wroxham with his wife Emma and their son Charles S. Green. When Charles, took it on in 1912, though only officially ‘devised to’ him in 1920, he was the 3rd generation of Greens to farm at The Beeches. Malting and brickmaking were both finished there before he started. I’m not sure exactly when brickmaking stopped, but some time in the late 19th century.

He married Christobel Gertrude Clark in April 1912 and they moved to the Beeches in 1913- I read a large extension was built there in 1912. Christobel had moved from London to Norfolk when her father, Harry Lewis Clark, took on the Maid's Head Hotel Norwich. The Clark home was "Riverscroft" not far from ‘The Grange’ in Wroxham. Charlie and Christobel would have known each other well since they were also both active with the sailing club on Wroxham Broad. She helmed and successfully raced Bubbles, number 3, a 14-foot forerunner of the ‘Norfolk’ dinghy. Tom Grapes told me Charlie Green was a good sailor, owning Yare and Bure ‘Purple Cloud’ (number 53) and more than one ‘Norfolk’ dinghy, one of which he had Percy Hunter build for him. He sometimes crewed for his wife and sometimes sailed with Clifford Kittle. He had boatsheds at the north end of Womack Water, near the staithe.

"Charlie Green’s boatsheds"

Always a mixed farm, there were three stock yards of beef cattle, fattened on Horsefen marshes in summer and in winter, housed, warm and dry, in the cattleyard. ‘Charlie’ grew oats, mangolds and swede for feed, wheat and barley, and was a bit of an entrepreneur in his first year, taking up the Dutch financial incentive to trial sugar beet for their newly operational factory at Cantley. Dutch workers were brought over to teach the Norfolk farm labourers how to harvest the beet by hand. Wherries such as the Albion would take the cargo, up to 40 tons, when the midships would be underwater and skippers needed gum boots. Sugar beet from local farms was transported to the Cantley factory by wherry from Womack until the mid 1950s. The waste pulp produced during processing was returned to the farms as cattle fodder, which might eventually replace mangolds and turnips.

One of the larger barns housed a circular horse-operated threshing machine. A horse, or horses, would power the machinery by walking in a circle to turn the gearing attached to the machine. They could thresh wheat, barley, oats and peas and process from up to ten times the amount a man could do in a day -about 80 bushels compared with 8. A bushell was by volume 8 gallons. Men were still needed to walk the horses, load the crop and collect the grain. Some claimed that malting barley was bruised and the straw broken, so many farms continued to thresh by hand flail.

reference: Susanna Wade Martins in “Changing Agriculture in Georgian and Victorian Norfolk”.

14th March 1914 Charles Wilkerson died age 78, having lived in the “dwelling house near Green’s Malthouse” for 40 years. He had seen his family grow, most marrying and moving away. His work was finished and he had lost a son and wife. I wonder what thoughts he might have had about the impending War. He was buried (plot G81) in St Catherine’s, Ludham on 19th March. When he died his daughter Margaret was able to stay on in the cottage until her death in 1940, aged 77.

The 1915 electoral register shows that George William Tidman moved from Lower Street, Horning to High Street, Ludham with his wife Bernice Maud and daughter Emily Maud. He was a wherryman. We know Charlie Green had cottages there so it may have been one of them.

In his will of 1920, William F. Green made provision for his wife to be paid £300 in equal quarterly payments ‘out of the farm at Ludham, devised to his son Charles Green.’ The statute tells us it comprised “farmhouse, granary, barns, stables/ buildings, land, arable pasture and marshland and the staithe and shed thereon, 218 acres, occupied by C.S. Green, and 2 cottages adjoining the stackyard, belonging to the farm, occupied by C.S. Green or his under tenants, and also nine thatched cottages, gardens and outbuildings (occupied by: Newton, Knights, Trivett, Police, England, Phillipo, Johnstone, George and Jermy)”, and also the Malthouse site near Womack Broad, then unoccupied. Tommy Thrower remembered the row of cottages on the High Street belonging to Charlie Green.

The 1921 census, this time recording the lane as “Womac Road”, shows Charles S. Green, 36 years 3 months, living at The Beeches with his wife Christobel Gertrude, 30 years 6 months, and a servant Christobel Reciller, 22 years 6 months. Deeds of Womack Cottages state that on 16th November 1921 the mortgage debt of £4,500 was transferred to Mrs Ethel Alice Gill, with interest of £46. The deeds also show that in 1922 the farm and cottages were purchased by Charles Spurgeon Green. Following his father’s death in June that year, having had The Beeches ‘devised’ to him in the will, maybe Charles paid off the Beeches mortgage debt by selling the Wroxham Grange Estate? Probate was granted on May 7th 1923 and on 10th July 1924 H. Edrich ‘authorised the satisfaction’ of the 1902 mortgage’.

Margaret Wilkerson now had new neighbours in the middle cottage, George, Bernice and Emily Tidman. A 1921 directory says the family were “near the malthouse” from that year due to his work, having moved from Ludham Street. George was a farm labourer doing ‘Heavy work’ and at times a wherryman.

Emily Tidman (http://www.ludhamarchive.org.uk)

Photograph of Emily aged about 7, “found in the empty house”, maybe by Pop Snelling?

I found in the 1921 register of electors that Sarah Ann Trivett (widow) lived in Womack Cottages ’near the malthouse’ and had the right to vote because she lived there due to her work. Using the census I found that she was the mother of farm manager Alfred James Trivett. The 1921 census lists another son Reginald Matthew Trivett, 17 years 10 months, living there, working as ‘farm servant’ for Charles Green, and two of Sarah Ann’s daughters were also living there but working as domestic servants for other employers. Daughter Elsie May Trivett 16, was domestic servant for Alethea Dale at the post office, daughter Gladys Sarah Trivett, 14years 4 months, was a domestic servant for Ruth Wenn, in an 8 roomed house in Horsefen Road, presumably Fenside or Womack House. Another daughter, Marian, 27, lived and worked in Horsefen Road at Little Holland for Frederick A. Canton and his wife. In 1928 Reginald was still in the cottage with his mother. The register says ‘O O’ for her, showing that she is the occupier connected with her work and he is ‘R’ or resident. Reginald married and moved out in 1930. The cottages remained in the same occupancy for the next few years, Margaret Wilkerson, the Tidman family and Sarah Trivett with Reginald. Mrs Alexander at The Manor employed Emily for a while.

By 1922 there was a bus service and that came from Yarmouth. Beulah Gowing recalled that the driver would sleep overnight at the King’s Arms, before returning the next day.

Candles and coal fires continued to be the norm until electricity was brought to the centre of the village in about 1926, and only to the outskirts after another few years.

Between them the village shops sold most of the villagers’ daily requirements. Still to be found were blacksmith, harness and saddle maker, mill wright and wheel wright, butcher, baker, carpenter, builder, grocer, draper and haberdasher, general stores, shoe repairer, fish smoker, chimney sweep and coal merchants, Post Office and carriers, as well as in keeping with the times cycle sales and repairs and a motor garage.

The shopkeeper would bring what you asked for to the counter, and if necessary slice, weigh and wrap in greaseproof or sugar paper. Besides foods you could find oil lamp wicks, mantles and chimneys, oil and paraffin, lead paste for a cast iron stove, tobacco, cigarettes, clothes, mending items, ointments, talc, home cures and medicines, vets’ products, soap, soda, metal polish, paint and brushes, distemper and general hardware. In addition, in 1937 there was an undertaker, a barber and a hairdresser and fish and chip shops.

Every age group would pick blackcurrants, along the Horning Road to Wroxham and at How Hill. I imagine the scene would not have changed much since the 1880s. Fingers stained purple, bodies aching but a joyful feeling when paid cash in the hand for each full punnet picked.

On 6th February 1932 Percy Hunter bought land from Charlie Green, close to the marshes, enabling him to create his boatyard and bungalows for himself and his two sons Stanley and Cyril, ‘Sevenoaks’, ‘Reedland’ and ‘Green Corner’ respectively.

About 1933 there was a severe outbreak of Measles, Scarlet Fever and Diphtheria amongst the children of the village, and as a result Sunday Schools were cancelled. 1938 yet another Measles and Chicken Pox epidemic affected services and schools in the area.

In the 1933 Kelly’s Directory Charles Green, [who had had a telephone installed] was one of about half a dozen major land holders in total doing well, whereas up to about 1920 there were many more, smaller farms. The smallholdings were gone, smaller farms sold and either amalgamated into other, larger farms, or built on.

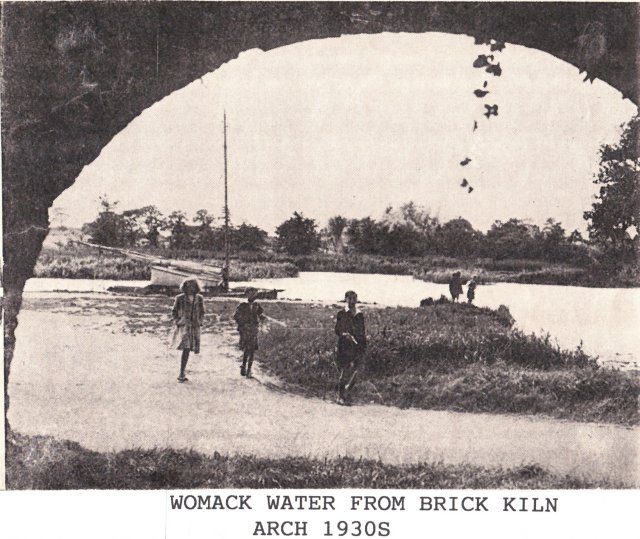

The conical brick kiln chimney had long since fallen into disrepair and was removed in the 1930s, though the arches remained and became partly covered and overgrown. They can be seen in many postcard photographs of this corner of Womack Water. For decades local children loved to play there. They used to jump up and down, race round and round, then hang on the trees growing on top.

Newspaper Photo Brick kiln arch. (http://www.ludhamarchive.org.uk)

Mike Fuller says David Gabriel told him he's the boy in the foreground.

There was a deep pond at Pit Corner, opposite the junction of Old Mill Lane and the Yarmouth Road. Beech Farm horses would drink there, and steam engines would fill up their tanks. Charlie Green described it as ‘bottomless’ and it was the source of many stories relating to the swallowing of man, horse and cart, never to be seen again! There was also a slipway at Womack where horses could walk or wade in, to drink and cool off. As a teenager in the 1940s, Beulah Gowing had led the circus ponies down there to drink. Next to Latchmore Lane where the 5 Bungalows are was a shallower pond that would sometimes dry out in the summer, but there was some good skating on it during the winter. Hemp for making ropes and sacks was once grown on Latchmore Field also known as ‘Thoroughfare Piece’ so possibly that pond was used for washing it.

A footpath ran across the field, which stretched from Pit Corner to the back of the Street houses. It was rough pasture with sheep grazing amongst gorse in later years, as recalled by Tom Gabriel. The path emerged onto the High Street, in more or less the same place as the passageway opposite Ludham Garage does now. Part way along were two small cottages on one side and the bowling green given by Charlie Green on the other, behind the cottages on the street, near where “Cat’s Whiskers” is now. In addition, there were three cottages with nice front gardens set back from the High Street, lived in by Beech Farm employees: the Perfects and the Trivetts, and Mary Harmer. Before widening and alterations in the 1970s the Yarmouth Road at the top of Horsefen Road passed on the other side of the oak tree at the current Mardling Seat. The tree stood at the corner of Beech Farm’s small horse meadow, on the edge of ‘Thoroughfare Piece’, where the fair used to be.

(There were just two years, 1952 and 1953, when it was held in Staithe Road, on the field belonging to Manor Farm where there is now a caravan site.) The funfair toured locally in the summer between June and August and visited Potter Heigham before arriving in Ludham. ‘You paid at the big gate and there were stalls including rides and a shooting range on three sides of the field.’ The fair was run by Walter and Jack Underwood. Jack was also known as ‘Rhubarb L. Smith’ and had it painted on his "Cakewalk" ride. It comprised two walkways moving both up and down and backwards and forwards, making it hard to keep your balance. You could stay on as long as you liked, providing a good spectacle. The speed and music were adjustable. There were also swing boats and dodgems.

Helen Watson remembers the “delicious Hot Cross Buns from the baker in Horning on Good Friday and when the fair came to the field on Green's Corner a few weeks later, the treat of ‘Fair Buttons”- large ginger and white vanilla biscuits.

At the time of the 1939 Government Survey Alfred James Trivett was Horseman at Beeches Farm age 50, becoming farm manager in the 1940s. He lived in one of the farm’s High Street cottages, behind the “Cat's Whiskers”, with wife Ada Gertrude, 46, and their three children: William G. age 20, a motor mechanic, Lesley (Larly) Trivett G. age 19, working as “heavy” farm worker, later becoming farm manager himself, and Victor age 13 who was at school. One of their neighbours was Robert J. Perfect (born 1878) who was 'second horseman' on the farm, living with his wife and daughter. Another neighbour was Bazel King, who used to sell fresh fruit and vegetables for his employer at the staithe.

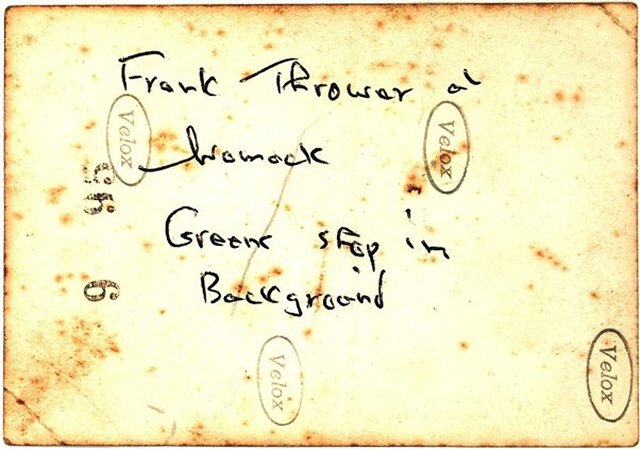

Charles Green also had a shed as a farm shop at the ruined brick kilns. Frank Thrower is pictured sitting outside it, aged about nine or ten.

Caption on back of photograph

Frank Thrower at the staithe, Green's shop behind, about 1937. (http://www.ludhamarchive.org.uk)