|

Memories

of War-time Ludham and working at

Walton Hall Farm with Sid Clarke,

artist.

|

Memories of Sid Clarke. These memories were recorded on tape on 5th December 2005.

Sid grew up in Ludham during the war. His father farmed at Walton Hall Farm and Sid worked there until 1971 when he obtained the tenancy of Grove Farm. Sid grew dried flowers and vegetables.

Sid was also a keen artist specialising in landscapes. He later bought a barn at Grove Farm and turned it into a studio and gallery. Paul Howell MEP opened the gallery in 1993. His paintings have sold all over the world.

The Gallery is opened 1993

My father, Herbert, was a really good footballer and played centre forward for Ludham, and when he retired he had a very good write up in the paper.

I played too. One year we won three big cups. In those days we didn’t have changing rooms – we used to change on the bus. We usually played cup matches in the evenings. The last of these three cup matches, we won. We were so excited. We hopped on the bus and still had our socks and boots on We got to the Kings Arms, hoping to go home, have a shower, get changed, come back and have a few drinks. When we got to the Kings Arms, the landlord, Billington, stopped the bus, got on, and said, “Right chaps, give me the cup. I want you all in the pub.” He took the cup in, stood it on the bar, and God knows what he put in – bottle after bottle in. He got all the players up to the bar and we all drank out of this great cup. I have never seen the village and the car park so packed tight with people at that pub. You couldn’t move. We had quite a following in those days. There would be people all the way round the pitch for a match. Then Arthur Gower displayed those big cups in the butcher’s shop for a year with all our blue and white colours.

When my father packed up playing football we all took up clay shooting at Earlsham Gun Club on a heath. My father got really good and I got into the British Open Championships. I took my son with me. It was the first time I had ever been in a big championship. The club had been invited – this was at Somerlayton. There were people from all over the British Isles. I didn’t think I had a chance. The first was ‘bolting rabbit’. There is a trap one side and a trap the other. You shout pull and a clay comes out from one side and bounces. When you hit it, one comes out from the other side. I watched these chaps in front of me miss most of them and I thought I would make a real fool of myself, but I hit 9 out of 10. However from there I just went downhill, and did little else in the rest of the competition. That was the day I damaged the nerve in my ear. I did a bit of game shooting after that, but then decided that I’d rather see the pheasants flying around. I packed up shooting, but my father carried on nearly until he died, and he was even then a good shot.

I was born in Staithe Road in 1939 in the house next door to what had been The Spread Eagle.

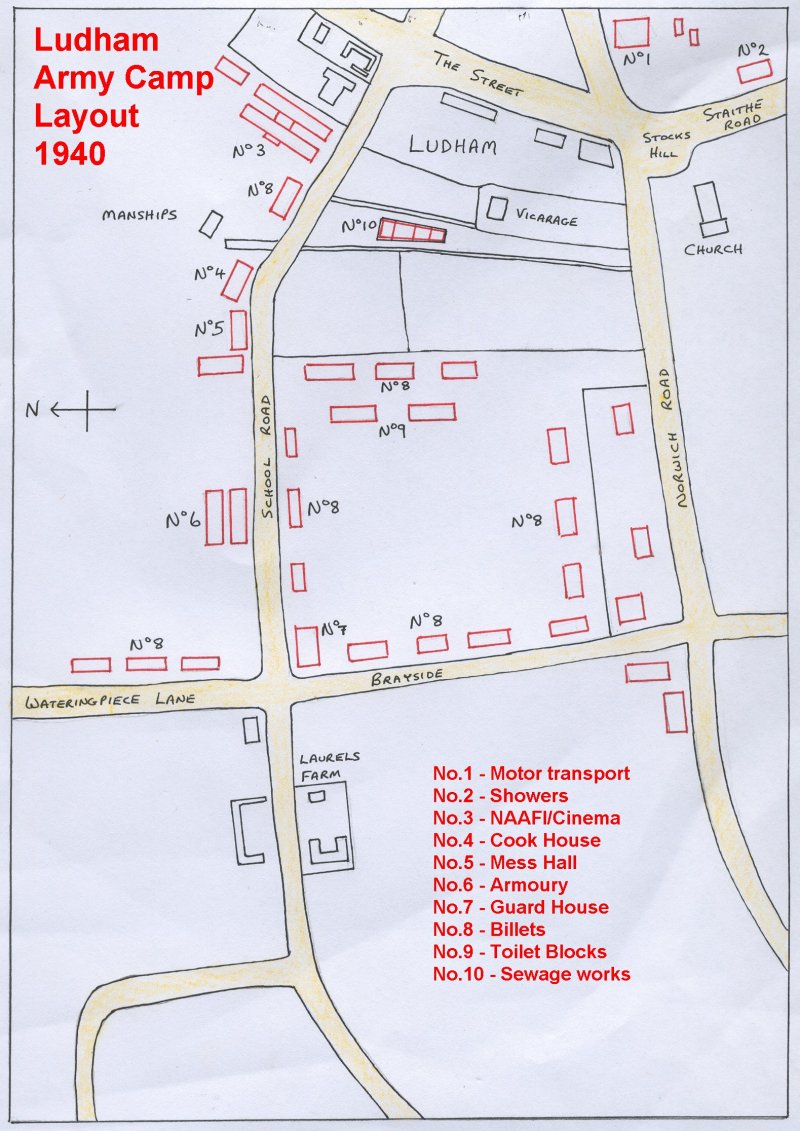

One of my first memories concerned the army buildings that were opposite us. There were Nissen huts and such like all over the village, and this was living accommodation for soldiers in the Manor. (This would be near No2 on the map below)

There was always a gap in the fence at that time, where the new surgery is now. The army put rolls of barbed wire there. Me and a friend, - we must have been about four or five, - it was before we went to school. It didn’t worry us at all. We used to creep through there, through the very long grass, and watch the soldiers.

There were two big guns there – don’t know what sort they were but they must have been anti-aircraft guns, because they were pointed upwards, and we would go across, climb onto the seats and play with the wheels. We didn’t really know what we were doing. The guns were moving around. The army realised something was up but they just couldn’t figure out who was doing it.

About a week or so later, we did it again. But the next time they were waiting for us. A soldier grabbed us by the scruff of the neck, both of us, and marched us into this Nissen hut and there was a big sargent sitting there, and he gave us such a telling off . He really shouted. I can still remember what I said. “Please don’t tell my mum”.

On the way out, there was a big box of empty cartridges from the rifles, and I said, “Can I have some of these?” “Get out of here,” he said.

I also remember when the plane crashed between Throwers shop and the butchers. I was quite small, and I told my mum there was a big fire in the village. There was quite a crowd there and they were trying to pull the engine away from the shop, because there was a butchers shop next to Throwers.. There was a big wooden garage where the King’s Arms car park is now. We were standing there and I looked in. There was the pilot laying there on a stretcher, waiting for the ambulance. Yes I can remember that with all the smoke going up.

I can also remember when my sister was small and in the pram, my mum used to go for a walk, and we’d walk so far up to Fritton on the back road. It must have been getting near the end of the war. The American big bombers, when they had been shot up would land pretty nearly anywhere. There was one quite close to the road, and there were loads of holes in the tail. I can still remember that.

Another one over shot the runway and came right across Catfield Road and into the field. It’s strange because we used to have a house on Latchmore Park (my daughter has it now). We used to let it and at one time there was an American there, for about two and a half years. I asked him if he was over here during the war and he said “Oh yes I was at Norwich. I was in the military police in the war”. I asked him if he ever came to Ludham, and he said, “two or three times”. His business in civilian life was an undertaker, and he said his job was to get the bodies out and wash the planes down. That really brings the nasty business of war home to you.

The Herbert Clarke on the war memorial was my grandad's brother, killed in the First World War. My Grandad and my father would never talk about the past.

One of the earliest memories I have of my father is of a big man in uniform in a peaked cap. He was stationed at Scapa Flow in Scotland. I didn’t see him until I was two or three. I remember my mum saying,”Your Dad is coming home tonight, you can stay up”. There was a big knock on the door. I ran to the door, opened it and took one look and cried my eyes out. I’d never seen him before, and there he stood with his rifle. We came across a photograph of him with a peaked cap an his coat, with my mum and me sitting on her knee – I could hardly walk I should think – I must have been about two and a half to three.

Also we had a shelter in one of the back rooms. Once we heard the siren go off and we heard this plane coming over, but nothing happened and then we heard the All Clear.

I remember Tommy Grapes telling me that he and Frank Thrower would climb a stack up on the Yarmouth Road, by the houses on the hill. They would climb onto there and look over the airfield and watch the planes landing. Tommy knew all the names of the planes. Once there were a lot, we think because the Bismarck was making a run up the Channel and they were sending anything up they could to try and stop it.

1947 was the really cold winter. I was about nine or ten. When I came home from school, my job was to grind mangols. I would change, have my tea and then I’d get a lantern and go out and grind the mangols so they were ready to feed the cattle next morning.

My father was a good skater as well (so was my grandfather). That year especially, because we could do nothing on the farm, we were skating all the time. My grandad gave me some old skates and Father skated to Thurne. He used to say, “If it bends, it breaks”. All the kids had skates when we went to school. One winter, down on Womack, Russel Brooks fixed batteries and lights on the ice at night and we would play ice hockey.

I can remember 1947, we were snowed in. You could only walk. I remember father saying, “You want to make the most of it. There is a warm front coming over and there’s going to be a thaw.” . I went onto the river and ws really disappointed because the sky was just black. I thought it was going to rain. What happened was the warm front came it was snowing, and the warm front got pushed back again and it carried on freezing for another three weeks.

When I was at Walton Hall Farm, I used to feed the cattle and you would get easterly winds, and once they were set in in the winter time, they stayed. It would be freezing.

When Paul Howell opened the Gallery in 1993, 600 invitations went out and I was farming at the same time. The idea was that the cars were going to be parked in the field behind here, about an acre of grass. We had a terrific thunderstorm, and there must have been six inches of water on that grass just as we were due to have that opening. I just didn’t know what to do. I rang up my neighbour who has the field over there, and he said to park the cars on the meadow over there – which we did. It was a real worry, but it actually went OK. We had the Eastern Daily Press here and my friend who does all my printing, he was here too. In the end the Eastern Daily Press camera didn’t work, so my friend got all the photos. The plaque (which is now inside the gallery) was screwed on outside the gallery ready for Paul Howell to open it, and the wrong date had been put on it. Most people seemed to notice it, but Paul Howell’s head just covered the date in the photos.

When we were at Walton Hall Farm, Pop Snelling came down to find out about it and Mr. Berry could remember bricks and pieces of footings in the fields. We looked for them but could find no sign of them. There used to be a big hall in fathers field. Walton Hall Farm, Ludham and Walton Hall Farm Catfield, the bricks were used to build those, so we were told . She thought that the knapped flint on the front of Walton Hall Ludham, might have come from St. Benets, as with the Stone House near The Dog.

At Walton Hall, I had three sisters, and I’m fairly sure there were seven bedrooms. The ones at the back were small, and I think when we first started ther, my father kept some chickens in there until my mother complained of the noise – she couldn’t sleep. I didn’t say anything to my sisters, until long afterwards, because I used to sleep in the back, then there was a spare room, then my sister had the next one. Then I was moved into the middle one, and the times I woke up. I could hear somebody breathing. It was just as though there was somebody in the bed, as loud as anything. I never did say anything. Then I mentioned it once and my sister said, “I’ve heard that”.

Even here in our old farmhouse (Catfield), which goes back earlier than the seventeenth century with lots of bits added on. It was quite a wreck when we moved in, but we did it up. It has never worried me, but in one of the bedrooms you could smell smoke, tobacco smoke. We thought it must have been the pipe smoke from next door. But I remember one night when my wife was out and the kiddies were small, I dozed off and woke up smelling smoke. I jumped up and opened the door but couldn’t see anything, everywhere was just white. So I don’t know whether it was me or what.

This happened with my mother and father. We used to have an orchard and stored the apples in one of the bedrooms. I would go to bed, go in there and get a big Bramley, and eat it in bed. I’d put the core under the pillow, but I’d forget it and my mother would find it.

Another thing there was a Maribella plum tree in the yard. There was a tin shed, and I used to climb up the shed and into the tree when I was supposed to be helping on the farm. My father would be looking for me saying, “Where on earth is he?” All he had to do was look down and see the pips and he would have seen me. But I kept quiet.

When we played football we would go into the Kings Arms, and he knew we here under age. He would say, “When a policeman walks in, - which they did, - do not touch your drink. There was a big latch on the King’s Arms door, and every time we heard someone coming in, everyone would stop drinking and look. The policeman would walk in one door and out the other. We wern’t doing any harm. When we were round about twelve or thirteen we would go round to the Baker’s Arms. We used to go in the back door, to Harry Warren and get a bottle of brown ale or light ale. That pub was really old. It was fairly empty most of the time, just a few old locals in there. It had like church pews and a slate floor and no pumps. They kept the beer in the cellar and I’ve seen his lad come up the steps from the celler with three pints in each hand, and not spill a drop.

I wouldn’t have got this gallery if I hadn’t been a farmer. I was one of the first to diversify. This farm was a County Council Farm and we got help from them